March Fungi Focus: Bracken Map and other Little Black Dots and Smudges

There are times when one does begin to wonder whether one has tumbled too far down the rabbit hole of mycological obsession. Though the Spring months might seem something like a drought period for many in search of curious fungi, they are all around us and all year round. For the hardcore few, the next few months in particular are a time of rummaging through hedgerows and peering at dried twigs, grasses and herbaceous stems in search of what effectively appear as little more than black dots. From then on, it is a just a small step away from the full-blown insanity of lichenology.

This month’s focus is on the more common and recognisable of these obscure types, which all fall within the category of ascomycetes: these are the spore-shooter types that develop their spores internally, typically in tube or flask-like sacs and in batches of eight, as opposed to the basidiomycetes, where the spores grow externally on cell-like structures known as basidia, typically in groups of four, which drop off as they mature.

Patellaria atrata, growing as inconspicuous black dots on a dead fennel stem, with the spores arguable more interesting looking than the fungus itself.

Patellaria atrata, growing as inconspicuous black dots on a dead fennel stem, with the spores arguable more interesting looking than the fungus itself.

I’ve written quite lengthily about various groups of ascomycetes in previous posts, but despite the fact that they far outnumber the basidiomycetes in terms of prevalence and the proliferating number and variability of species – which include the colourful goblet-shaped Green and Turquoise Elfcups, the hard black woodwarts and tarcrusts, and other less noticeable things like Sycamore Tar Spots and Holly Speckle) – many consider them a no-go area due to the inedibility of the majority of them, not to mention the fact most are very difficult to even see, unless one is looking specifically for them, yet alone identify.

Few have common names, and even the Latin names change with alarming regularity as individual species find themselves reclassified or split up into numerous subspecies. The obvious exception here is that prized edible, the Morel (Morchellan esculenta, although there are a few other lookalike species), one of the few that make it into spotters guides and foragers handbooks.

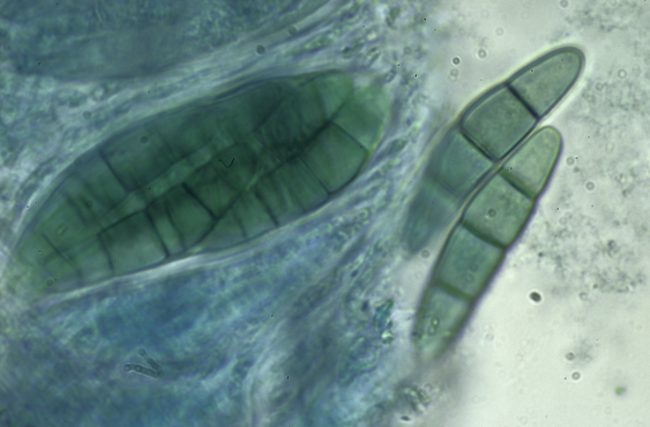

The spores of Bracken Map developing within its ascus, with their characteristic crescent shape, relatively large size and multiple segments.

The spores of Bracken Map developing within its ascus, with their characteristic crescent shape, relatively large size and multiple segments.

To really get to grips with the subject would take the kind of life-long fanaticism and fastidiousness displayed by the likes of Peter Thompson, the author of Ascomycetes in Colour (2013), who has evidently spent years driving around the country in search of photographic examples of the numerous nondescript specimens that can be found on specific hosts such as dead grasses, leaves and other organic material. It took literally a lifetime of research before the husband and wife team of Martin B. and J. Pamela Ellis devoted their retirement from teaching to put pen to paper for their landmark Microfungi on Land Plants: An Identification Handbook, first published in 1985 with a revised and enlarged edition appearing in 1997. Though it’s technically been out of print for years, the book remains a must-have for serious mycologists, giving an exhaustive list with detailed illustrations of the type of species one might find on a wide array of specific hosts, and secondhand copies are accordingly pricey. There’s also been more recent scholarly books such as Bjorn Wegen’s up-to-date and even more comprehensive Handbook of Ascomycota (2017), but again, this is a specialist publication intended for an academic readership and priced beyond the range of all but the most curious of amateur naturalists.

The foreword of the revised 1997 edition of Ellis and Ellis refer to microfungi as “ones which require the use of a microscope to see their variety”. Nevertheless, a microscope isn’t always necessary for the identification of a number of common types if you can ascertain their host. For example, over the next few months, if one looks closely at dead nettle stems, one might spot the tiny tangerine-coloured fruiting bodies (ascocarps) of Calloria neglecta, an ascomycetes fungus specific to them.

Two very similar looking species grow on ash keys: Diaporthe samaricola, grows on the seed part; the smaller Neosetophoma samarorum only grows on the winged part.

Two very similar looking species grow on ash keys: Diaporthe samaricola, grows on the seed part; the smaller Neosetophoma samarorum only grows on the winged part.

An even more extreme example of host specificity is Diaporthe samaricola, which over the winter months appears as miniscule black dots, less than half a milimeter in diameter, on the dried winged seeds, or keys (‘samara’) of ash trees. However, they will only appear on the seed part of the ash keys. Another fungus, Neosetophoma samarorum, produces eruptions of even smaller dots on the winged parts of the keys. The two will often appear side by side. They have no adverse affect on the health of the tree in question, although there is another ascomycetes that does have a notoriously detrimental effect on its host - Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, responsible for Ash Dieback and detailed in a previous post. Its small, white nail-shaped fruitbodies can be found on the blackened twigs and petioles at the foot of the infected tree around June.

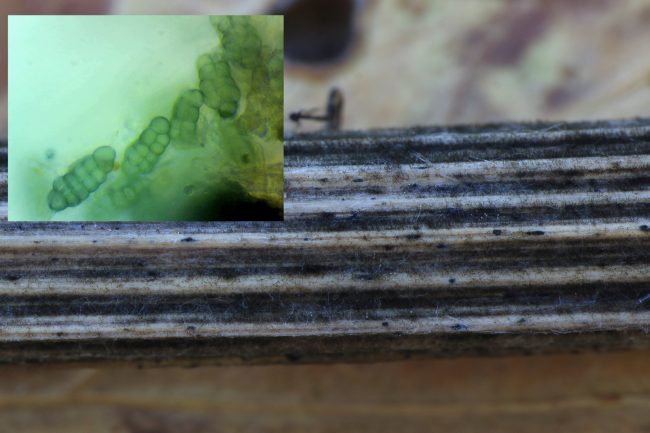

Bracken Map (Rhopographus filicinus) is another commonplace and instantly recognisable species that is host specific. It can easily be spotted at this time of year in most places where you find dead bracken, just prior to a new season’s growth sprouting up to replace the last, but actually one can find it all year round. The reason for its name is self-evident, as it grows in elongated spreading black blotches that eventually merge to form irregular shapes like countries on a map.

Dead bracken stems throughout the year can be seen hosting the tell-tale ascocarps of the Bracken Map.

Dead bracken stems throughout the year can be seen hosting the tell-tale ascocarps of the Bracken Map.

These blotches are the ascocarps, the fruitbodies from which the spores are released. The are described as pyrenomycetous, meaning that like the tarcusts or woodwarts or commonly-spotted Cramp Balls (Daldinia concentria, aka King Alfred’s Cakes), they are hard, brittle, and often carbonaceous, optimised to continue releasing spores over a relatively long period of time during the late-winter and spring months when the weather is relatively dry and temperatures start increasing, and yet there’s little greenery about to shelter them from the dry wind and lengthening hours of sunlight or get in the way of spore dispersal.

Each of these fruit bodies contains numerous tiny ‘perithecia’; flask shaped pits in which the asci sacks and the spores that develop within them are housed and are kept from dessication. The spores are released from holes known as ‘ostioles’ in the top of the perithecia that cover the black surface of the Bracken Map. If one looks really closely, one can see that the ostioles in the case of the Bracken Map are elongated along the length of the bracken stems.

The ostioles from which the spores are released can just about me made out when the ascocarp is looked at extremely closely.

The ostioles from which the spores are released can just about me made out when the ascocarp is looked at extremely closely.

The shape of the ostioles are a key feature in identifying other pyrenomycetous fungi, as detailed in my 2020 post on Woodwarts, Blackheads and Tarcrusts. It’s just as well, because there are many other types of such fungi that are not quite as distinctive-looking as the Bracken Map, and often much much smaller. I’ve been scrutinising various hedgerows recently, and noting that despite their superficial similarities, the seemingly identical black dots that appear on, for example, elder or hawthorn, are often very different species from those that appear on the woody dead stems of clematis or hogweed or other plants.

Fortunately, for those with a microscope, these kind of ascomycetes do have very distinctive spores that often serve as much better means of identification, in consultation with the literature cited above, than the actual ascocarp fruitbodies. As mentioned, basidiomycetes produce their spores externally on basidia, growing like apples from trees almost, and so they are typically asymmetrical and one can note the vestiges of a kind of stem by which they were attached to the basidia. The ascospores of ascomycetes tend to be much more symmetrical, often much larger and in some cases much more complex, consisting of multiple cells in different arrangements.

These tiny specks on a dried hogweed stem could be anything, but the complex multi-celled spores compare with a species called Pleospora phaeocomoides.

These tiny specks on a dried hogweed stem could be anything, but the complex multi-celled spores compare with a species called Pleospora phaeocomoides.

The spores of the Bracken Map are a great example of this – they are 27-35x7-8 microns in size, making them about three to four times the size of a typical mushroom-shaped basidiomycetes type like a Brittlegill – and to put this in perspective, they are just a smidgen smaller than the 40-micron threshold considered visible to the naked eye, or about the size of a small grain of salt. They are crescent shaped with 4-8 segments, and look rather like croissants under the microscope.

I’ve detailed a scant few of these types of fungi prevalent over the next few months that can at least be recognised without recourse to a microscope. There are, however, at least 10,000 ascomycetes species found in the British Isles alone, so this is clearly a subject few will want to engage with too thoroughly. There are a couple of other more readily identifiable species that might catch the attention of the woodland walker, however, but I’ll leave these for next month...

Bracken Map

Bracken Map

Comments are closed for this post.