August’s Fungi Focus: Blackberry Leaf Rust Fungus (Phragmidium violaceum)

We have now entered those glorious few weeks in the foragers’ yearbook when the proliferation of brambles across the country is at last yielding its fruits. For the bulk of the seasons, however, Rubus fruticosus can be viewed as little more than an annoyance, an invasive native with barbed, snaking canes that spread across pathways and woodland floors to form impenetrable thickets, snare up by passers-by and crowd out surrounding biodiversity (See ‘Native dominants or botanical ‘thugs’ in woodlands). Or so it might seem. You will have probably noticed the tracks left by moth caterpillars munching on bramble leaves. Any blackberry-picker will also be well aware of the close association brambles seem to have with stinging nettles. Both attract a wide variety of insect life during their flowering months. Deer and small mammals such as dormice, not to mention numerous bird species, are also the beneficiaries in terms of food and shelter of the bramble’s vigorous growth .

From a mycological perspective, blackberry bushes support a surprising array of fungi, although admittedly mostly of the type that doesn’t attract much in the way of attention and appreciation. Some types grow from the dead canes just as they might any other woody debris. Take, for example, the tiny unidentified Mycena ‘Bonnet’ mushroom depicted here, which was found growing from a small fragment of bramble stem just a few inches in length buried beneath several centimetres of leaf litter and tiny twigs.

Other fungi are more exclusively linked to a bramble host, including a couple that fall within the little-loved category of the rust fungi. These are a category of pathogenic species that only grow on living plants and, I can put if no better than Eugenia Bone in her book Mycophilia: Revelations from the Weird World of Mushrooms, “are so called because a leaf sprinkled with their reddish spores or small brown pustules looks like rust.”

To the naked eye, it would be pretty fair to say that one rust looks pretty much like any other of the 7000 or so species out there. The fungus grows on the surface or within the living tissue of the plant, and without going into the more meticulous methods of looking at details like spore size and shape through a microscope, can usually be identified by its restriction to the range of plants on which it grows. There’s many a gardener who could identify Puccinia allii, or the Onion Rust, for example, which manifests itself on the leaves of onions, leeks and other alliums as powdery deposits of orange spores or tiny blistering galls that turn from orange to black, depending on where the rust is in its life cycle. Puccinia urticata is the name of the rust found exclusively on stinging nettles. (As an aside, rusts are a little different from smuts, which instead go for the plant’s reproductive parts and as well as causing tumorous growths on fruits and flowers, are recognised by their darker, dirtier and thicker-walled spores that look like a sooty “smut”.)

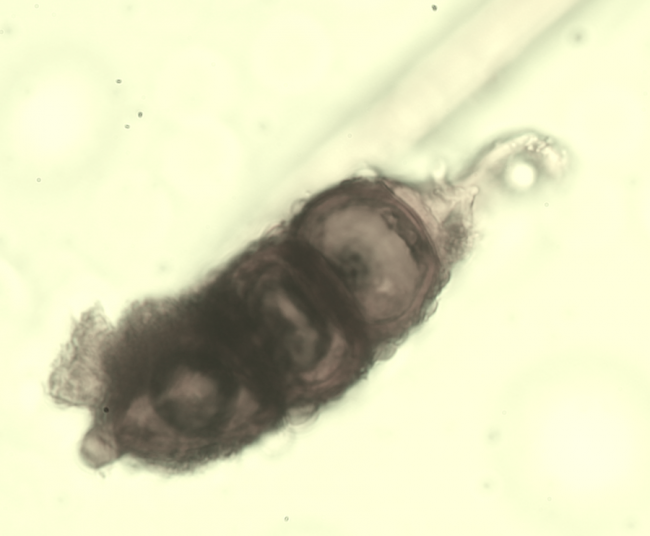

Rust fungi produce different forms of spores across their life cycles. The types known as teliospores are the resting or overwintering state, though which the fungus is spread to new plant hosts by insects, wind or water. These thick-walled teliospores appear segmented and grow on fine thread-like hairs from the fungal hyphae, rather like microscopic potatoes growing from the roots of a potato plant.

A segmented teliospore from the Blackberry Leaf Rust

They are actually relatively big as far as fungi spores go, typically just large enough to be discerned individually under a hand lens. The biology is kind of complex, and a more detailed look at the diversity, range, habitats and habits of rust fungi might be best left for another day. Nevertheless, there is certainly a lot of rust about in the Spring and Summer months when there is fresh foliage to feast on – so fungi fanatics who wish to colonise a relatively uncharted area of expertise might want to note that it is prevalent at the times of year when other more alluring forms of mushroom and toadstool aren’t.

For an idea of what you might be letting yourself in for, there’s a dauntingly comprehensive list of rust fungi with photos and other details on the website ‘Plant Parasites of Europe: leafminers, galls and fungi’. It is worth pointing out these parasitic fungi are harmful to their hosts to varying degrees. Their presence is often signalled by yellowing leaves and other visible signs of wear and tear. Certainly if you are a farmer dealing with commercial monocultures you need to be extremely vigilant against those like the wheat rusts that can wipe out large proportions of annual cereal crops, or Hemileia vastatrix, the Coffee Leaf Rust that has been devastating plantations across the world. We might see these rust epidemics as symptomatic of the same changing climate conditions and increase in transportation of plant material across the world as last month’s fungus of focus, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus , responsible for Ash Dieback .

Others, however, are restricted to the kind of hosts that we are not so bothered about and live in accordance with the plant’s growth cycles, particularly annual plants, so really only appear on weakened plants whose leaves or stalks are dying back anyway. We might therefore not be too concerned about things like Alexander’s Rust (Puccinia smyrnii), and indeed some may even find strange beauty in the swellings caused by its growth.

This pinkish orange-dusted swelling on an Alexander’s leaf can be identified with some certainty as Puccinia smyrnii, or Alexander’s Rust, on the basis of its plant host alone

They are a part of the natural cycle of the seasons, like the Tar Spots that appear on sycamores and maples at this time of year – although it is interesting to note that the cause of these, Rhytisma acerinum, is one of the ascomycetes fungi types discussed in last month’s post, which release their spores through tube-shaped asci, whereas the rusts are all basidiomycetes that produce spores through specialist club-shaped cells called basidia.

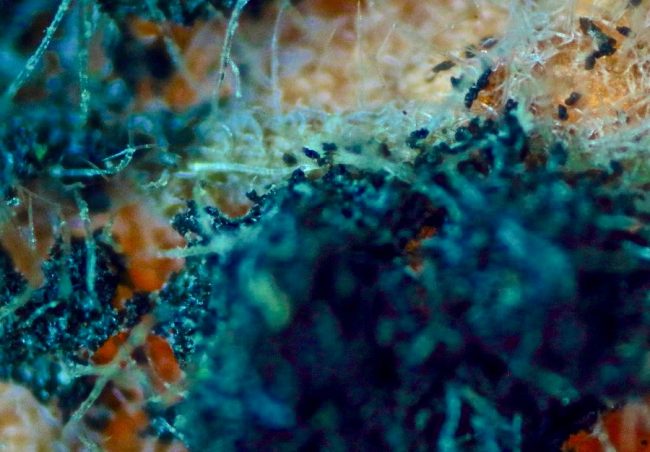

Kuehneola uredines under the lens on a blackberry stem

Brambles are prone to two specialist rust fungi. Kuehneola uredines is one, and as its common name of Bramble Stem Rust highlights, is mainly apparent on the stems of blackberries and other Rubus species such as raspberries, dewberries, loganberries, et cetera.

Blackberry Stem Rust and Blackberry Leaf Rust on the same blackberry bush

Its orange spores are about large enough to be distinguished individually, a little smaller than grains of sand perhaps. It also manifests itself on its host’s leaves, where it emerges on the upper surface as yellowish or pale orange spots. Effectively, however, it looks much and of a muchness with any other rust unless looking at microscopic details. The other more distinctive one is Blackberry Leaf Rust Fungus (Phragmidium violaceum), also known as the Violet Bramble Rust, which is much in evidence on in the form of the wine-coloured blotches that appear individually peppering the upper surface of leaves and can spread enough to fuse together.

Bramble Leaf Rust (Phragmidium violaceum), or Violet Bramble Rust

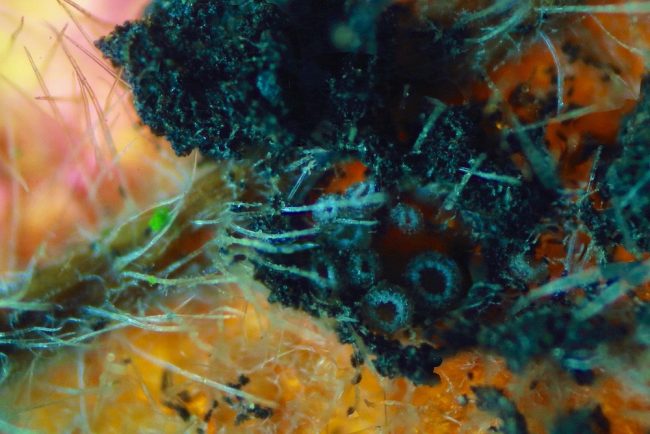

Look underneath and you’ll see individual uredinium, the name given to the pustules formed when the hyphae of a rust fungus bursts through the surface of a its host and which consists of a reddish or black mass of hyphae and the teliospores carried upon it.

Detail of uredinium showing hyphae and teliospores as they grow on the blackberry leaf

In this species, the dark teliospores consist of 3-4 sections, and again they are just about visible to the keen-eyed amongst us: at around 80 microns in length (0.08mms), they are about 10 times larger than your average mushroom spore.

Both of these rusts are pretty common, and while clearly they sap the plant of vigour, certainly not enough to warrant much concern about the future of their hosts. That said, Blackberry Leaf Rust has been has been introduced as a biological control for invasive European blackberries in Australia, New Zealand, and Chile While we might view rusts as unwanted freeloaders in great scheme of the world, the Blackberry Leaf Rust provides a fascinating example of the parasite parasitized. It was a tweet by Lukas Large, Natural Sciences curator of Birmingham Museum, that drew my attention to the fact that if you look closely at the dark blotches on the bottom of the leaf formed by the uredinia, you can sometimes find a tiny associated cup fungi, about a tenth of a millimetre in diameter, called Mollisina oedema.

The cups of Mollisina oedema are about a tenth of a millimetre across

This seems to be a pretty obscure fungi. It is not included in Peter Thompson’s 2013 book Ascomycetes in Colour, for example, and a Google search for Mollisina oedema doesn’t throw up very much. Nevertheless, after scoping out several blackberry leaves, it wasn’t long before I found a cluster of these tiny cups for myself. This would indicate that Mollisina oedema is pretty common, but like so many fungi, little known because it is little seen and little searched for. In fact, it was first discovered and recorded under the name Peziza oedema as far back as 1850, by French mycologist John Baptiste Desmazières (1786-1862).

What better illustration might there be of how the world is so much more varied and complicated than one could possibly imagine? Who knows what the exact nature of the relationship between Phragmidium violaceum and Mollisina oedema is? Nor any of those other obscure species listed on the Bioimages webpage under the heading “Interactions where Rubus fruticosus agg. is the victim or passive partner (and generally loses out from the process)” ?

Indeed, just as William Blake saw the world in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower, we might find a mycological microcosmos in a bramble bush. And for those not yet convinced of just how amazing fungi are, might I suggest one get out gathering fruits before another fungal associate kicks in, the grey mould Botrytis cinerealm then put a kilo of blackberries in a bucket with a kilo of sugar, add a sachet of one of the great wonders from the Kingdom of the Fungi, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and a gallon of water. Within a couple of months you could well be sitting with a glass in your hands marvelling at mankind’s own miraculous relationship with the natural world.

Blackberry Leaf Rust uredinium under the lens showing hyphae and teliospores

Blackberry with rust

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

We live on 2 acres here in Hawaii upcountry. Our property is being surrounded and invaded by Himalayan blackberries. It is almost impossible to get rid of them by just cutting them down.As you know they have large roots that spread out underground and it is popping up everywhere. I am in my 70’s and do most of the yard work myself. I would appreciate your opinion about introducing Violet Bramble Rust to kill it. If so where can I acquire some phragmidium violaceum? Thank you for all the good information!! Aloha

Excellent read and great pictures too. Thanks Jasper.

Thanks so much for your kind words. It is wonderful to hear these posts are appreciated! Hopefully there is a lot more scope to carry on with them – there are about 10,000 different species in the UK! And glad to hear the microscopy is also appreciated, as this is a skill I am currently very much in the process of refining.

With its combination of vivid descriptive writing and detailed, accurate science, I think the “monthly mushroom” makes a fascinating series. Since retiring (and spending more time in my woodland), I have concentrated on improving my knowledge of wild green plants, but I know little about the fungi. As a former medical microbiologist I have some experience of looking at fungi under the microscope,so I appreciate the inclusion of photomicrographs

Hi Suzanne. To be honest, I’m not sure how efficient phragmidium violaceum actually is as a biological control. The fact that it was so common in the UK and doesn’t seem to hamper the growth of brambles suggests it isn’t very effective, and personally I wouldn’t want to recommend introducing another potentially alien invasive in the form of a fungus to somewhere like Hawaii. I can imagine however how annoying having a huge tangle of brambles to deal with on your land might be.

Jasper Sharp

29 March, 2020