Climate change, forest fragmentation, fire and disease

The Earth is warming as a result of the release of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels, leading to a period of rapid and significant climate change, which is seen as an existential threat to humanity by many. It is possible that the tipping point has been reached, where the effects of global warming, such as the loss of polar ice sheets, are unstoppable. The most dire ‘predictions’ think that cities, industries, countries, and perhaps our species will be lost.

Climate change is not new and variations in the patterns of weather have provoked the collapse of regimes and cultures throughout recorded history. Social and economic constructs have unravelled and populations have declined.

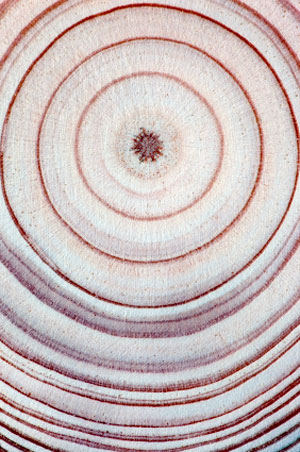

We know something about some of these past changes in weather and climate from various sources. Dendrochronologists have used wooden artefacts and examined material from many different tree species to build up a picture of when the climate was favourable for tree growth (then the rings would be widely separated from one another), and when conditions were more difficult perhaps due to drought or cold. Many of the studies on tree rings were undertaken by "Mike"Baillie (Professor Emeritus of Palaeoecology at Queen's University of Belfast). He was instrumental in constructing a chronology of tree-ring growth that extended back some seven thousand years. He has proposed that climatic downturn seen in many parts of the world in circa 540 AD was due to an explosion of a meteor in the upper atmosphere*. This gave rise to an 'envelope' of dust and ice that surrounded the Earth, resulting in a drop in global temperature. This can be traced in tree ring samples across Europe, Siberia, North and South America and Scandinavia. The unseasonable weather gave rise to crop failures and famine.

We know something about some of these past changes in weather and climate from various sources. Dendrochronologists have used wooden artefacts and examined material from many different tree species to build up a picture of when the climate was favourable for tree growth (then the rings would be widely separated from one another), and when conditions were more difficult perhaps due to drought or cold. Many of the studies on tree rings were undertaken by "Mike"Baillie (Professor Emeritus of Palaeoecology at Queen's University of Belfast). He was instrumental in constructing a chronology of tree-ring growth that extended back some seven thousand years. He has proposed that climatic downturn seen in many parts of the world in circa 540 AD was due to an explosion of a meteor in the upper atmosphere*. This gave rise to an 'envelope' of dust and ice that surrounded the Earth, resulting in a drop in global temperature. This can be traced in tree ring samples across Europe, Siberia, North and South America and Scandinavia. The unseasonable weather gave rise to crop failures and famine.

Tree ring data from Mexico and other parts of North America indicate that there was a severe drought in the sixteenth century, and that this drought extended from Mexico to the boreal forest, from the Pacific to the Atlantic Coast. The only areas exempt from the drought were coastal regions. This extended drought coincided with two major epidemics (in 1545 & 1576) of cocoliztli. This was a swift and lethal disease, with a high death rate.  It seems to have been a form of haemorrhagic fever (as is Ebola), and was probably responsible for the deaths of millions of the native population of Mexico. It has been suggested that the virus ‘jumped’ from rodents to humans. The rodent population had exploded when wet years followed prolonged periods of drought. Again tree ring data support the idea that the drought was occasionally interrupted by wet years – as in 1545.

It seems to have been a form of haemorrhagic fever (as is Ebola), and was probably responsible for the deaths of millions of the native population of Mexico. It has been suggested that the virus ‘jumped’ from rodents to humans. The rodent population had exploded when wet years followed prolonged periods of drought. Again tree ring data support the idea that the drought was occasionally interrupted by wet years – as in 1545.

Other scientists have drilled down into the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, and have extracted ‘cores’ of densely packed ice. The deepest ice in Antarctic cores might be hundreds of thousands of years old. By examining the ratios of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the different ice (compacted snow) layers, they are able to determine how patterns of precipitation have fluctuated around the poles. This gives information about the Earth’s average annual temperature over the centuries. Plus, bubbles trapped in the cores contain minute samples of the ancient atmosphere. These, when analysed, reveal data about the concentration of carbon dioxide and other gases in the atmosphere.

An alternate source of information about past climates and weather events is oral or written records. For example, the log books of ships (in the days of sail) can yield detailed information about wind and rain across the world's oceans.

By studying both qualitative and quantitative information from a variety of sources, it is clear that the Earth’s climate even in relatively recent times (the last 2000 years) has not been static. For example, it is now clear that cooling extended across the Northern Hemisphere from the 13th century onwards.

The causes of the cooling have been attributed to

- cyclical changes in the orientation of Earth’s rotational axis,

- decline(s) in solar radiation,

- fluctuations in oceanic and atmospheric currents, and volcanic eruptions

The “Little Ice Age” is a term sometimes applied to these periods of cooling, a number of which occurred at different places and times. Glaciers probably expanded but it was not an ice age in the true meaning of the term - where ice sheets covered vast areas of the globe. Even the coldest decades of this period probably did not see a cooling that exceeded an annual drop in temperature of more than 0.5o C. Parts of northern Europe were subjected to years of long winters and short, wet summers, whereas in southern Europe droughts occurred but also long periods of heavy rainfall. For those who lived through it, this was no trivial matter. Malnutrition and famine were commonplace and there were outbreaks of plague which spread across parts of Asia and Europe, and were responsible for the death of millions. Some have suggested that ‘unstable / changing weather’ promoted oscillations in the rat populations; rats act as vectors for the fleas that spread the plague.

The “Little Ice Age” is a term sometimes applied to these periods of cooling, a number of which occurred at different places and times. Glaciers probably expanded but it was not an ice age in the true meaning of the term - where ice sheets covered vast areas of the globe. Even the coldest decades of this period probably did not see a cooling that exceeded an annual drop in temperature of more than 0.5o C. Parts of northern Europe were subjected to years of long winters and short, wet summers, whereas in southern Europe droughts occurred but also long periods of heavy rainfall. For those who lived through it, this was no trivial matter. Malnutrition and famine were commonplace and there were outbreaks of plague which spread across parts of Asia and Europe, and were responsible for the death of millions. Some have suggested that ‘unstable / changing weather’ promoted oscillations in the rat populations; rats act as vectors for the fleas that spread the plague.

The environmental challenges we now face are far greater than those of the past. Recently, we have witnessed outbreaks of the Ebola virus. The virus can exist in animal populations, possibly such as bats, without affecting them. It has been suggested that changing weather patterns (dry periods followed by heavy rain) have resulted in an abundance of fruit - which has attracted apes and bats to the ‘glut’ of food, providing opportunities for inter-specific transfer of the virus.

The change in climate may have also resulted in bats extending their range and therefore increasing contact with humans (directly or indirectly). We can contract the virus by eating or handling an infected animal.

The United States Agency for International Development has noted that many of the new, emerging, or re-emerging diseases are “zoonotic” — that is they originate in animals. These range from AIDS, SARS, to the various flu strains that have threatened us (e.g. H5N1 and avian flu). Animals, which may have harboured diseases for years, are now coming into contact with humans, often because of deforestation and land clearance to support growing populations. Human activity [such as mining, logging, ‘slash and burn’ agriculture and road building, plus the demand for firewood] drives deforestation. Deforestation means animals (like bats) are more likely to find ‘homes’ closer to human settlements. Sierra Leone lost much of its forest in the early part of the twentieth century.

Other diseases are known to be climate sensitive, such as malaria, dengue fever, West Nile virus, cholera and Lyme disease. These are expected to intensify as climate change progresses, temperatures increase as do ‘extreme events’. Malaria (caused by the protozoan - Plasmodium) has always been a significant killer, but it is expected that it will increase in range with climate change and the season for transmission (from Anopheline mosquitoes) will also increase.  Greater rainfall offers more places for the mosquito larvae to live and thrive. By the same token, the mosquito (Aedes aegypti) that spreads dengue fever will be favoured by warmer and wetter weather.

Greater rainfall offers more places for the mosquito larvae to live and thrive. By the same token, the mosquito (Aedes aegypti) that spreads dengue fever will be favoured by warmer and wetter weather.

Droughts or floods will affect crop yield, which in turn can result in malnutrition, so making people more susceptible to disease. Flooding can also provide not only breeding grounds for insects but can result in the contamination of water supplies with faecal matter, resulting in diarrhoeal diseases like cholera.

Dry conditions ‘creates’ fuel for forest fires that end up fragmenting or destroying forests and woodlands. This last year or so has seen some extreme examples. Australia is no stranger to fire; bushfires have been known for thousands of years by the indigenous peoples (often triggered by lightning strikes). These last few months have seen fires that are unprecedented in scale and ferocity; and the ‘bushfire season’ is not yet over.

Whereas in the past, bushfires were mainly associated with grasslands, burning non-woody herbaceous plants, the fires this time have affected areas where fire has rarely burned in the past, including rainforests, wet eucalyptus forests, and dried-out swamps (where the water table has dropped). Areas rich in Eucalypts are more likely to catch fire because of the volatile and highly combustible oils produced by their leaves.

The litter beneath these trees is rich in organic compounds such as phenols. These slow down the microbial breakdown of the litter and dead leaves, so a layer of dry, combustible material accumulates. Some five million (plus) hectares of land has already been burnt. Vast tracts of forests, woodlands, trees, shrubs and grasslands have been consumed by the fires.

The fires have been fuelled by

- The extreme heat,

- A prolonged drought (Australia has experienced one of the driest Springs since records began over a hundred years back) and

- Strong winds.

These hotter and drier conditions are associated with climate change and have made the country’s bushfire season longer and much more dangerous. Record breaking temperatures have been recorded and mid-December saw the hottest day ever recorded (an average temperature of 41.9 C. The hot weather was also accompanied by strong winds which fanned the flames, spread the fires and blew smoke across major cities.

Australia is not the only country affected by fires. Sweden has a lot of forest and woodland, much of it dominated by Spruces and Pines. Again recent record breaking temperatures and drought across many parts of Europe have put large areas of Swedish forest at risk. Rainfall in Sweden in 2018 was been dramatically down - approximately a seventh of the normal amount. In Summer 2018, there were some 50+ fires burning from the extreme north down to Malmo in the south.

Summer 2019 saw fire affecting thousands of square miles of boreal forest in Russia. Russia has the largest area of forest in the world; it covers some 40+ % of the country. Much of thi forest is remote and difficult to reach which creates particular problems when trying to control the fires. Strong winds spread the smoke and ash across the country; it affected cities such as Novosibirsk and Krasnoyarsk (each home to a million people).

woodland and forest as seen from the Trans Siberian railway

There have also been recent fires in the Amazon; these forests are often described as ‘the lungs of the world’. Fires in this region are to be expected during the ‘dry season’, but there has been the suggestion that some fires were deliberate (clearing for agriculture or mining ?). [The BBC published an interesting graphic of the fires.] Whilst some ecosystems ‘benefit’ from periodically experiencing fire - as it allows for regrowth; this is not the situation in the Amazon. The tropical forests of the Amazon have no adaptation to fire and suffer immense damage in consequence.

The fragmentation and the loss of forests / woodlands (across the globe) has been a concern for many years due to its effects on biodiversity and ecological processes. Fragmentation of woodlands and forests can be the result of;

- Farming and agriculture

- Timber extraction

- Construction of motorways / railways

- Housing

- Mining

To these human directed activities, we probably can now add anthropogenic climate change.

* others have implicated volcanic activity.

The links (in the text above) offer further detailed information on various topics but there is a lot of interesting material available on the web: e.g

- https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

- https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/geh/climatechange/health_impacts/index.cfm

- https://theconversation.com/bushfires-can-ecosystems-recover-from-such-dramatic-losses-of-biodiversity-129836

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/03/climate-crisis-seriously-damaging-human-health-report-finds

- https://climate.nasa.gov/news/645/climate-change-may-bring-big-ecosystem-changes/

and interesting to read David Attenborough's latest comments on Climate Change : https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-51252222

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

A well written and well explained article, if very worrying in content, who wrote it?

It’s been a long day and I’m trying to catch up on a backlog of emails. I really haven’t got time to read through this kind of drivel. There is nothing original in this article that a reasonably informed person hasn’t read a dozen times elsewhere. Forestry is a long term business and I need some constructive information about what I should be planting now for the next 50/100 years. All these articles indicate that the authors have no more idea than I have. If they have nothing to constructive to say then nothing is what they should contribute. I could research a few sources and write rubbish like that.

Larry Adlard

11 February, 2020