December’s Fungi Focus: Holly Speckle (Trochila ilicina)

I’ve written about the ascomycetes, or sac fungi, in several previous blog posts, but as well as giving a special festive twist to this December’s Fungi Focus, the Holly Speckle (Trochila ilicina) provides as good an opportunity as any other for a recap on the subject.

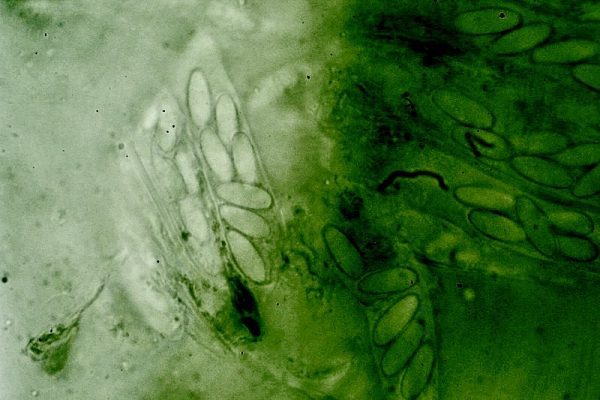

Quite distinct from basidiomyces, which produce their spores on specialised spore-bearing structures known as basidia found on the gills of our more familiar cap-and-stem types (or in the pores of the boletes ), the ascomycetes are characterised by the way in which they produce their spores inside tube-like sacs contained within specialised fruiting bodies known as ascocarps, which are then shot out dramatically like balls from a ping-pong ball gun into the atmosphere.

Ascomycetes present a huge, diverse and extremely challenging division within the kingdom of the fungi even for the most fervent mycologists. For a start, these ascocarps tend to be very small and non-descript.

The larger and more readily identifiable types include Cramp Balls, Deadman’s Fingers and Candlesnuff, although the morels and related types like the White Saddle (Helvella crispa) stand out as more obviously mushroom-shaped species.

THE WHITE SADDLE (HELVELLA CRISPA), ONE OF THE MORE STRIKING AMONG THE ASCOMYCETES

The vast majority of ascomycetes are more likely to manifest themselves as tiny black blemishes, pepperings of gelatinous dots or miniscule discs of various hues on dead organic matter, with many less than a millimetre in diameter on rotting logs. Not only are they easily overlooked, even if you are actively looking, but most are impossible to identify with any certainty without recourse to a microscope.

The substrate on which they are found, however, can play a considerable role in this process. The unsightly Tar Spots you see on sycamore leaves in late Summer, for example, are caused by Rhytisma acerinum , although it should be pointed out that this discolouration is a manifestation only of the fungi growing within the leaf, the so-called stroma (according to the dictionary definition, the “cushion-like mass of fungal tissue”) in which the spore-producing ascocarps develop. The ascocarps are really only fully formed during the winter months, appearing as a mosaic-like arrangement of black bumps on the surface of the dead leaves lying on the ground, which release their spores in time for the fresh leaf growth of Spring.

a "mature" Tar Spot (Rhytisma acerinum)

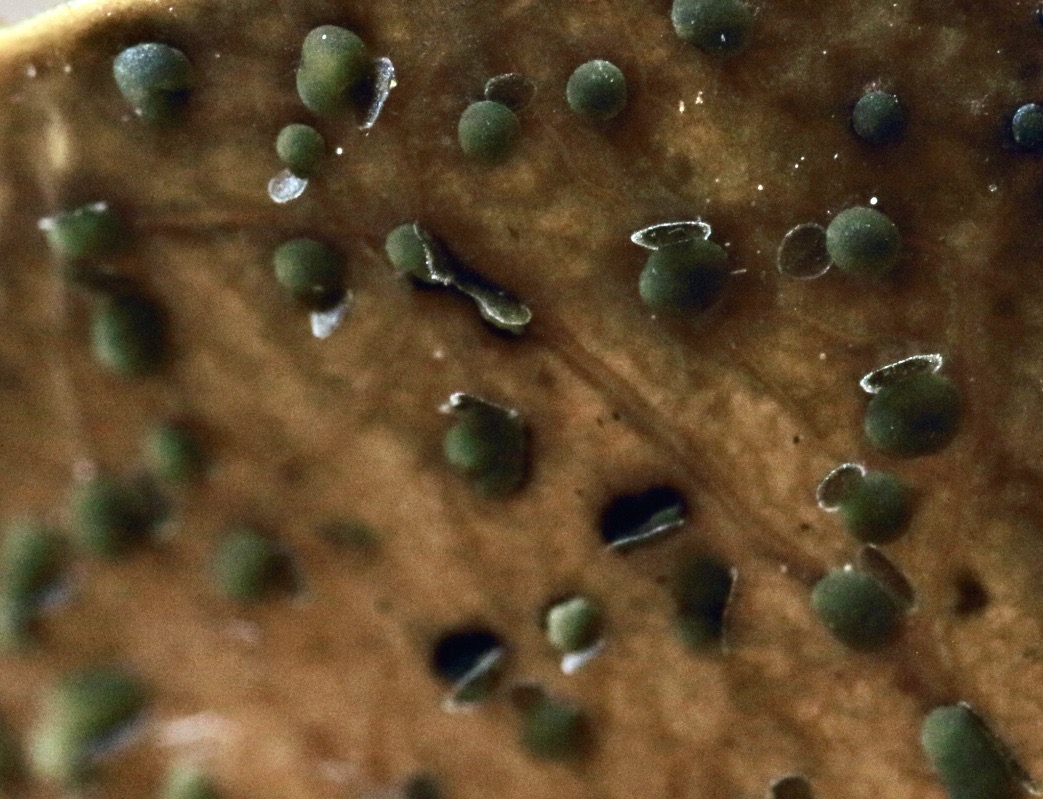

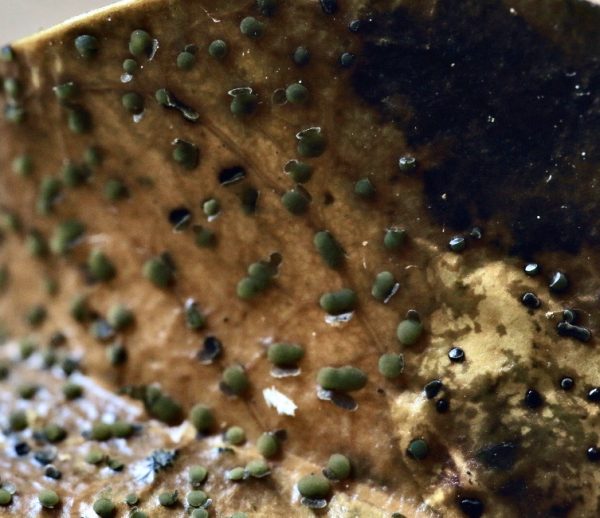

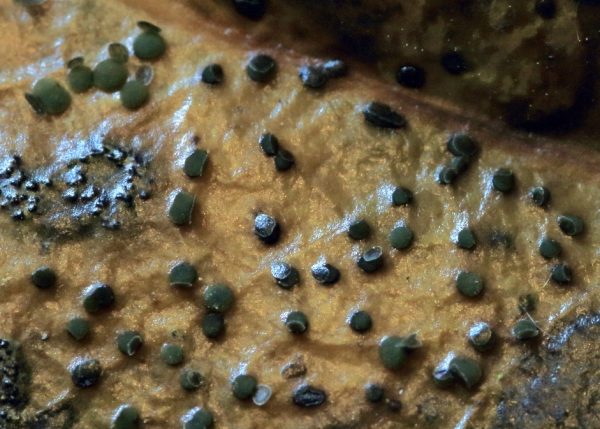

In a similar way, where there is Holly (Ilex), you are likely to find Holly Speckle (Trochila ilicina). It occurs pretty much all the year round, growing on dead holly leaves, although somewhat perversely given the seasonal nature of this blog post, it is more common in the warmer summer months. The “speckle” covering the leaf is comprised of a multitude of these ascocarp fruiting bodies: not dots or blotches but small brown or dark green pustules, each around a millimetre in diameter that rise from the upper surface of the leaf (not its underside). They are not particularly exciting to the naked eye, it is true, but a more close-up inspection gives a better insight as to how these function.

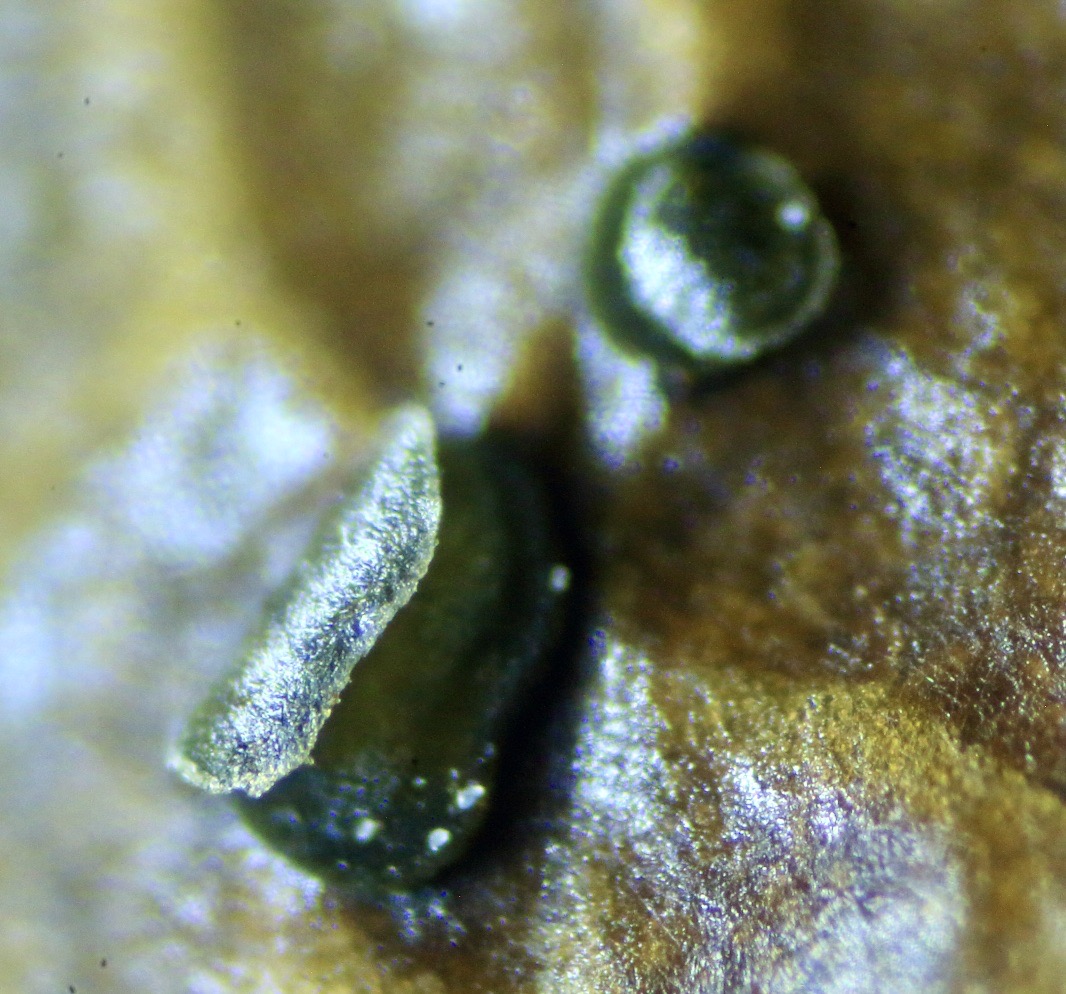

DETAIL SHOWING THE 'LIDS' OF THE APOTHECIUM HAVING FLIPPED TO REVEAL THE HYMENIUM

Among the tens of thousands of ascomycetes fungi, there are a number of differently shaped types of ascoscarp reproductive bodies that hold the asci structures from which spores are released. To keep things as uncomplicated as possible, I’m going to focus on just the one most common type known as the apothecium, which is basically a cup, cushion or saucer-shaped structure growing out of the substrate, either on a stalk or directly attached by its base, as is the case with Trochila ilicina.

MANY ASCOMYCETES ARE NOT READILY IDENTIFIABLE FROM THE ASCOCARPS, OR FRUITING BODIES, UNLESS UNDER A MICROSCOPE

The cups and discs of Peziza, Mollisia and Melastiza and the tiny tin-tack forms of Hymenoscyphus species were described in July’s Ash Dieback Fungi Focus . They typically have a flat or concave upper surface called the hymenium in which, if you look at a cross-section under a microscope, you can see the asci are densely packed and that these sacs open out onto the surface to fire out the spores. (A dramatic counterpoint to the apothecium type of ascocarp can be seen in truffles, which instead have self-contained spherical fruit-bodies known as cleistothecium: as these grow underground, there is no way of them releasing their spores into the atmosphere from an exposed upper hymenium surface, so instead the asci are contained inside them, and the spores only released once the fruits burst while passing through the body of a pig or some other hungry mammal).

Looking at the Holly Speckle under magnification and you can see that each of these individual “speckles” is an apothecium. These grow as cushion-shaped structures that form a hard flat upper surface skin. When the apothecium reaches maturity and the spores are ready for release, “the fungus tears away [the] more or less circular ‘lids’ of epidermis to reveal the hymenium”, as Peter I. Thompson describes in his Ascomycetes in Colour (2013).

CLOSE UP SIDE VIEW OF APOTHECIUM

As the wonderful new two-volume Fungi of Temperate Europe (2019) publication shows, the fertile hymenium revealed once this lid flips aside are initially a much lighter green-tinged yellow. (You can see a photo of this taken by one of the co-authors, Jens Peterson, on this Danish-language website). In my photos, all taken from the same leaf, one can assume that some time must have passed since the hymenium has been exposed, because it has gone a darker colour.

HOLLY SPECKLE APOTHECIUM, SHOWING HYMENIUM

As I’ve pointed out before, a lot of fungi, and particularly ascomycetes, tend to evade our attention because they are so small, obscure and superficially uninteresting. We might also say that it is probably due to its substrate that Trochila ilicina has become the most representative of the Trochila genus, which according to the rather sparse Wikipedia entry consists of 15 species. Of these, only Ivy Speckle (Trochila craterium) and Laurel Speckle (Trochila laurocerasi) seem to be distinguished enough to have been accorded names by the British Mycological Society , and also to have been check-listed in the otherwise exhaustive aforementioned Ascomycetes in Colour and Fungi of Temperate Europe tomes. At least these common names do provide a strong clue where to look if you are particularly interested in checking them off your list!

Which is not to say these fungi are not useful. Ascomycetes are essential decomposers, and we might imagine that Trochila ilicina is the primary agent involved in initially breaking down of the rather tough and durable holly leaf to the next level where the nutrients contained within it are made available to detritivores like worms and woodlice, or maybe even simpler organisms like bacteria and other fungi.

The Holly Speckle is not the only fungus restricted to holly leaf litter.

Holly Speckle

If you hunt around beneath these prickly evergreens this December, you may also be lucky enough to chance upon the tiny, perfectly-formed and rather rarely found Holly Parachute (Marasmius hudsonii). I never have myself, so we may have to wait at least another year before this forms the subject of a future fungi focus, but if I ever do, I wouldn't be exaggerating to say it would probably make my Christmas!

If you hunt around beneath these prickly evergreens this December, you may also be lucky enough to chance upon the tiny, perfectly-formed and rather rarely found Holly Parachute (Marasmius hudsonii). I never have myself, so we may have to wait at least another year before this forms the subject of a future fungi focus, but if I ever do, I wouldn't be exaggerating to say it would probably make my Christmas!

In the meantime, however, I will refer you to Pat O’Reilly’s page on his fabulous First Nature website featuring this distinctive and rather beautiful mushroom. While you are looking, please note in the top photo of his entry that the species with which the Holly Parachute is sharing its leaf is the Holly Speckle. It is a wonderful reminder of complex inter-connectedness of a natural world that still remains very much an uncharted mystery for so many of us.

Comments are closed for this post.

Very interesting, great depth of discussion; keep it up, I look forward to every entry

donald johnston

4 December, 2019