June’s Monthly Mushroom: Deer Shield mushroom (Pluteus cervinus)

After last month’s epic two-parter on the Elder Whitewash fungus, I’m reining in my focus to something more traditionally mushroom-looking this month. The recent combination of generally warmer temperatures coupled with the odd cooling cloudburst and resulting humidity has prompted the appearance of a number of mushroom sproutings in recent weeks, and one of my recent sightings has been the Deer Shield Mushroom (Pluteus Cervinus), which Roger Phillips’ Mushrooms and other Fungi of Great Britain & Europe says can be found from “early summer to late autumn, but also sporadically throughout the year.” I found specimens of this elegant looking species from October to mid-December last year and early May this year, so they are pretty prevalent throughout the seasons.

The Deer Shield is a common find on rotten stumps and logs in deciduous woodlands, and relatively easy to identify (I find that once you’ve positively identified a mushroom, you’ll usually recognise it pretty quickly next time you find it). Its alternate names of Deer Mushroom or Fawn Mushroom (related to the ‘cervinus’ part of the Latin name, meaning ‘deer’) come from the sepia, taupe or tan to more umber or dark brown colour of the top of its cap, but also the slightly velvety look that the darker fibrillose streaks radiating outwards from its centre give it. This upper cap surface is smooth to the touch when dry, with a greasy feel when wet.

You can see how the stems and the gill edges discolour as the mushroom ages

As any passing slug will reveal, however, this brown surface is actually just a layer of skin (or pileipellis in more precise mycological argot) and can easily be peeled off to reveal that the flesh beneath is white. The stem, which gets up to 10cm in length, about 1cm in diameter and has no ring around it, is also white, although it too is tainted by brown fibres running vertically towards its base.

"Passing slug"

Slug bites show the white flesh beneath the cap skin of the Deer Shield mushroom

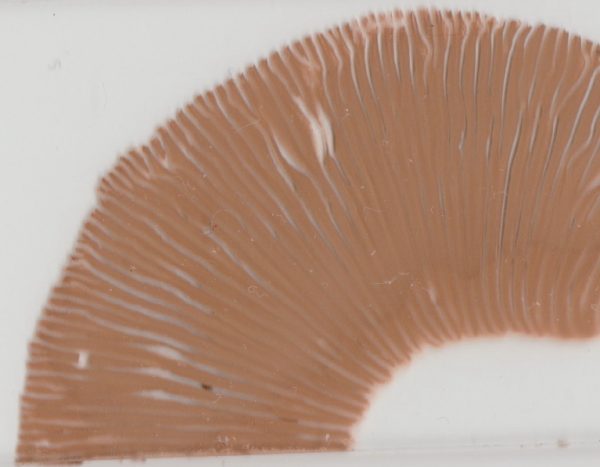

The cap starts out convex, around 4-5cm in diameter, rising and flattening as it expands to around 12-15cm to reveal its gills, which are free from the stem (that is they aren’t to it) and quite densely packed together. The gills are also initially white, before becoming a dull grey-pink then darkening around the edges with age. This discolouring is due to its spores, which are as pink, in a buff-or-beige-to-salmon sense of the word.

Note the gills are described as 'free' in that they aren't attached to the stem

We should never overlook the importance of spores in zeroing in on any specimen we’re trying to identify. All guide books will describe a fungi’s spore colour, and several will use it as one of the keys to direct you to the part of the book where any possible candidates are listed. For example, the Collins Gem: Mushrooms mini-guide first asks if the fruit body shape is a crust, bracket, club or umbrella shape; if it’s an umbrella shape, you are directed to the next section asking whether the underside has pores, teeth, is smooth or has gills; if it has gills, then the next section asks about spore colour, and if the spores are pink and if the gills are free and the mushroom is on rotting wood, then according to this book, it will either be a Deer Shield or its less common close relation, the Veined Pluteus (Pluteus umbrosus), distinguished by its minute scales on the cap surface that give it an even more velvety look and feel.

Deer Shield

Actually the Collins Gem guide only lists these two species, but Roger Phillips states there are 34 pink-spored Pluteus in Great Britain, such as the smaller yellow-coloured Lion Shield (Pluteus leoninus) or the even tinier Dwarf Shield (Pluteus nanus). But anyway, you get the gist of why spore colour is important.

Taking a spore print is easy enough. Just lie the mushroom cap gill-side down on a piece of white and/or black paper for a couple of hours and the spores will just drop down and leave their pattern. If the spores are pink, then it will be in the Pluteus family, unless it is in the considerably more sizeable Entoloma family, or ‘pinkgills’.

The buff to salmon pink sporeprint of Pluteus cervinus

The Entoloma family encompasses a vast array of species, most of them found on grasslands rather than in woodlands, and many of them of the commonplace LBM (‘little brown mushroom’) variety and notoriously difficult to identify.

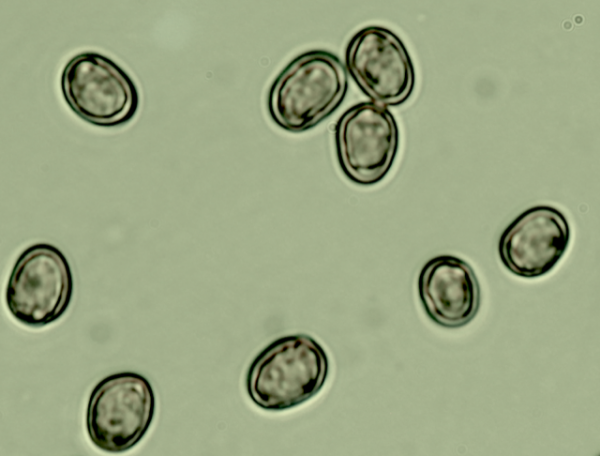

However, there also more striking examples that fall under the Entoloma umbrella such as the Wrinkled Peach , or edibles like Wood or Field Blewitts. I won’t go into the complexities of the family relationships here, because a lot of these related species keep getting recategorized and whole genera shifted around. What we can say is that the main difference between Pluteus and Entoloma can be seen under the microscope: spores from species in the latter family are angular, spined, ribbed, warted or have other protrusions, whereas Pluteus spores are smooth, broadly ellipsoid in shape and about 7-8 x 5-6 microns in size.

The spores are smooth and without ornamentation

If you do wish to go into the subject deeper, I refer you to Michael Kuo’s excellent piece on MushroomExpert.Com or Pat O’Reilly’s overview of Entoloma on First Nature.

Either way, a more obvious guideline for those without a microscope, as Kuo points out, is that as well as having free gills, Pluteus species are “are wood-rotting saprobes found on decaying logs” whereas the Entoloma have gills that join the stem and are usually “saprobes that help decompose forest litter, which means that they usually grow on the ground”.

The one exception where you will see a Deer Shield on the ground however, is that they can be seen very commonly growing on bark chippings, in kids play areas, mulched garden borders and landscaped public spaces such as shopping centres etc.

The Deer Shield Mushroom plays an incredibly beneficial role in forest habitats, actively breaking down dead wood and returning it to the soil system, then. Unless you are one of those types who eats everything just because its free rather than because of its taste, I wouldn’t advise it as an edible. I’ve tried it once and it can’t really claim it was worth the bother, the flesh too brittle and tasteless, and while I have given enough of a description here so that it might be easily distinguished between other similar looking species, it is worth remembering that there are many Entoloma that are poisonous, so the pink spore print certainly shouldn’t be the be-all-and-end-all of your identification process.

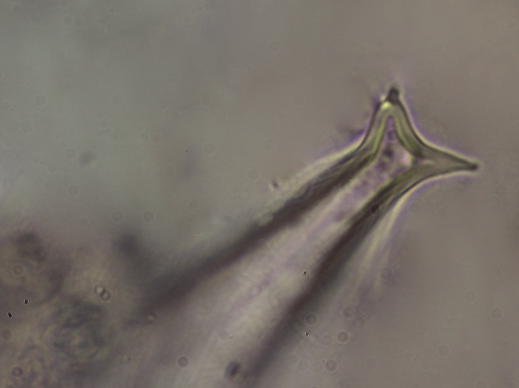

You won’t really need a microscope to be 100% positive that you have discovered a Pluteus cervinus anyway, but if you do have one, there’s one other fun little detail invisible to the naked eye that characterises this species, and which Pat O’Reilly on First Nature claims is another reason for the ‘Cervinus’ or ‘Deer’ part of its name. There are large cells called cystidia that can be found on the gills of those mushrooms that have gills, and in the case of the Deer Shield Mushroom they look a little like a deer’s head, with two horns sticking out the top.

Comments are closed for this post.