Medieval Woodlands: the Magna Carta and the Forest Charter

In the 13th century, "forest" land included fields, heathland, villages as well as woodland - Royal Forests were areas where very different and rather Draconian laws applied. Over the previous two hundred years a "forest" had become a royal hunting ground for the King and, by invitation only, the aristocracy and very strong restrictions applied to this land. By the beginning of the 13th century a third of southern England was designated as forest even though Royal Forests hadn't even existed before 1066: they were were set up and extended by successive Norman Kings. Royal Forests were so extensive that all of Essex was included at one point. Not only did ordinary people have fewer rights in forest lands but it was uncertain exactly what those rights were. This left an opportunity for kings to extend the size of the forest and enlarge their powers. Kings such as Richard and his brother King John, arguably England's worst ever king, took full advantage of this in extending their rule, but their power was constrained by that of the barons.

At the time of the signing of the Magna Carta (15th June, 1215 - 800 years ago) forest rights were a hot topic and an important element of the "great charter" was reducing the size of the forest and limiting the power of forest law. This famous charter promised that all the extra lands that had been claimed as forest lands during John's reign would have to be "disafforested", meaning that forest law would no longer apply to them. Offences under forest law were divided into two categories - those against the vegetation (the vert) and those against the game (the venison). In forest areas, freedoms were very restricted and it was an offence to enclose land, to clear trees or to put up buildings.  The penalties for breaking the forest law were severe and one could, for example, be killed just of the crime of stealing a deer.

The penalties for breaking the forest law were severe and one could, for example, be killed just of the crime of stealing a deer.

You can read the whole of the Magna Carta here, translated from the Latin into English. It is surprisingly readable and and not too long - the main forest-related clauses are 44, 47, 48, 52, and 53. This charter was followed two years later by the "Charter of the Forest" which was less focused on the rights of the barons and more not the interests of free men - it reiterated that much of the recently adopted forest was to be disafforested and explicitly gave rights to people living in the remaining Royal Forests. This charter also limited punishments that could be given by courts in forests - for example mutilation was abolished as a possible punishment. It was at this time that Verderers courts were set up to enforce the charter, and they are still in existence today in the New Forest in Hampshire and they play an important part in the management of New Forest National Park.

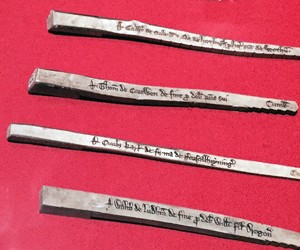

Life for everyone would have been a much more outdoor business in the 13th century: seasons and daylight hours would have dominated all daily routines in a way that we can hardly imagine today. Food and fuel for cooking or heating would have been largely found in the wild. Without the use of electricity, plastic and petrol, daily life in medieval England would have been different in almost every way. Woodland products reached into all aspects of daily lives. For example the tally sticks shown above as the featured image, would have been used in financial transactions - they were marked with the relevant numbers and then split longways so that each party took one half of the hazel stick which would then represent the receipt and counterpart in a transaction. Such a system would have been almost impossible to counterfeit. The tally sticks (image featured above) are part of the Magna Carta exhibition at the British Museum - "Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy" which is open until the end of August 2015.

At the end of the 13th century, in 1297, the forest charters and the Magna Carta were consolidated into the "Confirmation of Charters". This gave free men protection to use the forest for basic needs by permitting foraging by pigs (pannage), collection of firewood (estover), grazing of livestock (agistment) and cutting turf for fuel (turbary). Over the years the royal rights became less extensive and by Tudor times the forest laws were mainly protecting the timber in Royal Forests. But some parts of the Laws of the Forest remained in force right up until the 1970s when they were finally superseded by the Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Acts in 1971.

At the end of the 13th century, in 1297, the forest charters and the Magna Carta were consolidated into the "Confirmation of Charters". This gave free men protection to use the forest for basic needs by permitting foraging by pigs (pannage), collection of firewood (estover), grazing of livestock (agistment) and cutting turf for fuel (turbary). Over the years the royal rights became less extensive and by Tudor times the forest laws were mainly protecting the timber in Royal Forests. But some parts of the Laws of the Forest remained in force right up until the 1970s when they were finally superseded by the Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Acts in 1971.

Comments are closed for this post.