Monthly Mushroom: Hairy Curtain Crust (Stereum hirsutum)

We are well past peak mushroom season now, so you can expect some degree of slippage between the various specimens featured in these Monthly Mushroom posts and what can still be found out there in the wild in the month they are posted. Not quite yet, however. Due to a rather mild winter so far, touch wood, there is currently still plenty of interest popping up on lawns, pastures, tree stumps and amongst the leaf litter.

In any case, there is a whole swathe of fungi that should be coming into their own at the moment if you care to look out for them – although admittedly precious few willingly choose to do so. These are the crust fungi, sometimes known as patch fungi. Instead of the discrete mushroom-like reproductive bodies of our more familiar fungal finds, with their caps, stems and gills, these types manifest themselves on tree trunks, both dead and alive, or on fallen branches, as expanding leathery patches, gelatinous swellings or peeling skin-like layers of varying hues.

They are more technically referred to as resupinate fungi, from the botanical term meaning ‘upside-down’ or ‘upward facing’, because it is from these patches, the exposed “hymenial surface” or “hymenophore” that face upward and outward from the fungi’s woody host, that they release their spores.

They are more technically referred to as resupinate fungi, from the botanical term meaning ‘upside-down’ or ‘upward facing’, because it is from these patches, the exposed “hymenial surface” or “hymenophore” that face upward and outward from the fungi’s woody host, that they release their spores.

The various types in this category aren’t necessarily lumped together due to any biological kinship, but because of more obviously visible features, namely their shapes and growth patterns - in much the same way as the species encompassed by the terms ‘bracket fungi’ or ‘puffballs’ are.

It is not surprising that resupinates so successfully evade much in the way of interest or attention. Like our conventional mushrooms and toadstools,  they spend most of the year out of sight and out of mind, existing as a network of mycelium spreading within their chosen substrate. When they do appear, they can be seen everywhere within the woodland landscape, yet have few of the qualities that might warrant further attention. You can’t eat them, nor are you likely to even contemplate such a thing, and most can hardly be considered photogenic.

they spend most of the year out of sight and out of mind, existing as a network of mycelium spreading within their chosen substrate. When they do appear, they can be seen everywhere within the woodland landscape, yet have few of the qualities that might warrant further attention. You can’t eat them, nor are you likely to even contemplate such a thing, and most can hardly be considered photogenic.

They appear as various coloured smudges, coatings or encrustations that eventually bleed into one to form a larger whole, it is a tricky business to know where an individual specimen might even begin or end. It is also difficult to ascertain at what point in the fruiting cycle they are at. If you see what looks like a daub of whitewash on a standing tree or a thick cobweb pattern emerging beneath rotting logs, you could be for forgiven for mistaking it as the first visible flush of mycelium from any number of fungi that has yet to transform into something more recognisable.

In many cases this manifestation is as good as it gets though, with the fruiting body appearing as nothing more noteworthy than a pale-coloured layer of something mysterious but unmistakably fungal, something with a distinct air or rottenness about it. Even when fully mature, most lack much in the way of distinguishing features. The species of host tree and whether it is alive or dead might provide clues. For the vast majority, however, you will need to resort to looking through a microscope at such details as spore size and shape, the number of pores per square millimetre on its surface layer and other even more esoteric details to be absolutely certain of what it might be.

In many cases this manifestation is as good as it gets though, with the fruiting body appearing as nothing more noteworthy than a pale-coloured layer of something mysterious but unmistakably fungal, something with a distinct air or rottenness about it. Even when fully mature, most lack much in the way of distinguishing features. The species of host tree and whether it is alive or dead might provide clues. For the vast majority, however, you will need to resort to looking through a microscope at such details as spore size and shape, the number of pores per square millimetre on its surface layer and other even more esoteric details to be absolutely certain of what it might be.

It seems that there are literally hundreds of different species out there, although easy to understand why most field guides only devote a few pages at best to a choice handful of the more readily recognisable. Gerrit J. Keizer’s The Complete Encyclopedia of Mushrooms (1998) and Michael Jordan’s The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe (2004)  provide two notably comprehensive exceptions, with a daunting succession of pages devoted to photos of types with such cryptic names as Trechispora farinacea or Hyphoderma setigerum, that look, to all intents and purposes, identical, basically smears of white or beige or other just off-white colours with vaguely differing textures and folds.

provide two notably comprehensive exceptions, with a daunting succession of pages devoted to photos of types with such cryptic names as Trechispora farinacea or Hyphoderma setigerum, that look, to all intents and purposes, identical, basically smears of white or beige or other just off-white colours with vaguely differing textures and folds.

Very few resupinates have English common names, and if they do, these are neither particularly appealing nor revealing. The British Mycological Society website lists a couple of dozen deemed distinctive enough to warrant the honour, which include Enveloping Crust, Rusty Crust, Mothball Crust, Glue Crust, Bleeding Oak Crust, Jelly Rot and Yellow Cobweb.

Not all are quite so anonymous however. The striking deep blues of the Cobalt Crust (Terana caerulea), the jagged buff-coloured protuberances that comprise the Toothed Crust (Basidioradulum radula), and the radially-expanding scarlet gelatinous folds of Wrinkled Crust (Phlebia radiata) all definitely stand out amongst the drab grey-greens of the winter woodland. Many are even more striking when viewed up close and personal through the camera lens, revealing colours and textures quite distinct from their background substrate.

Wrinkled Crust (Phlebia radiata)

the Hairy Curtain Crust (Stereum hirsutum)

One of the most commonplace and instantly recognisable of the resupinates is January’s Monthly Mushroom, the Hairy Curtain Crust (Stereum hirsutum). This emerges initially in the form of ochraceous orange patches with paler edges, tending to buff or cream colour, that soon fuse together and, if growing horizontally from a dead hardwood substrate, eventually develop into densely packed, undulating shelves, which blur the dividing line as to what constitutes a crust and what constitutes a bracket fungi.

Hairy Curtain Crust

In fact, once fully developed, Hairy Curtain Crust is equally likely to be mistaken for other resupinates than it is with similarly commonplace brittle bracket types like the Turkeytail (Trametes versicolor, also known as the Many-Zoned Polypore), although even a cursory look will show ample differences. For example, there is something a little less cluttered about the way the Turkeytail grows outwards in fan-shaped brackets, the concentric zones on them more cleanly delineated into more muted shades of brown and grey, and their undersides pale cream and covered in tiny pores, unlike that of the Hairy Curtain Crust, where the hymenophore is smooth and only slightly paler than the top.

Turkey Tails

Aside from the colour, the key defining feature responsible for the hirsutum part of the Hairy Curtain Crust’s name is the fine downy hairs that cover its upper surface.

You may well have seen Hairy Curtain Crust growing on fallen trunks or branches or from stacks of logs. These are saprobic fungi, the mycelium feeding on dead wood and thereby responsible for its decomposition (there are other crust fungi, such as members of the pathenogenic Peniophora genus that are perhaps less benign, infiltrating living sapwood).

The question that will no doubt go through many people’s minds is perhaps not so much how many resupinates there are out there in the world, but who has actually bothered to go out and count and categorise them and to what end? Does anyone know what function these organisms perform in the wider ecological scheme of things? Some of the resupinates in the UK are included on Red List of Threatened Species, but one has to wonder how many people are actually looking for them and would know if they’d found them.

Resupinate fungi certainly represent one of the more challenging extremes of mycology, and one might be forgiven for thinking life might be just that little too short to concern oneself unduly with them. But are we perhaps missing out on a whole world of nature that might be of more interest and significance than we realise? If nothing else, the presence or absence of certain specimens might be indicative of the overall health of forest ecosystems.

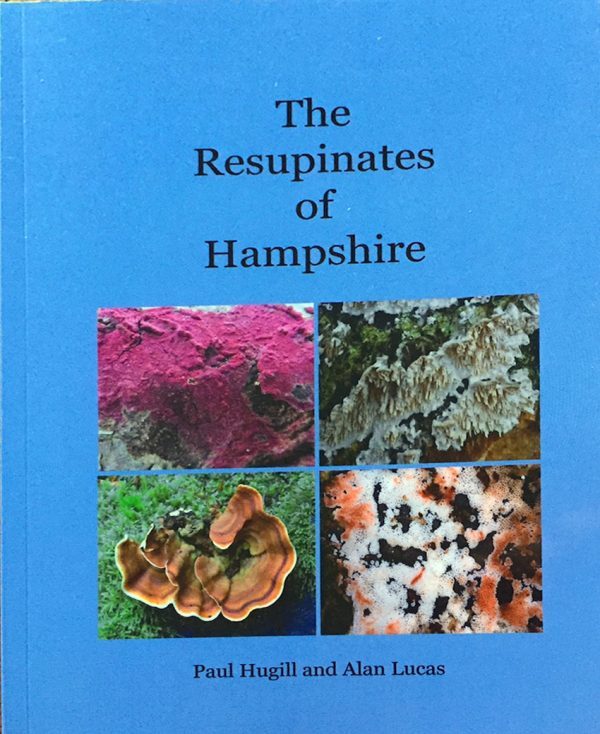

Certain figures from the Hampshire Fungus Recording Group seem to think they might be worthy of deeper consideration. Their website not only provides a useful online identification resource for those wishing to take the plunge, but two of its members, Paul Hugill and Alan Lucas, have also compiled the most complete printed work on the subject,

The Resupinates of Hampshire (presumably representative of the resupinates found in other counties within the United Kingdom). The second edition is just out, its 400 pages packed full of colour photographs and diagrams of microscopic features, although only seems to be available if you contact someone through the group’s website.

I, for one, am looking forward to digging into this tome, and shall heading out into the forest with fresh eyes over the coming months, because one of the other aspects of this type of fungi is that they appear regularly throughout the year. I hope to report back in the coming months if I find and photograph anything interesting!

Unidentified resupinate

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Stereum hirsutum not hirsutem!

Very good summing up of this group

my typo !

thanks for spotting

Blogs

2 February, 2019