November Fungi Focus: Amethyst Deceiver (Laccaria amethystina) and the documentary Fantastic Fungi

There has been such a diversity of interesting things popping up in the woods recently then fading right back almost as soon as they appear that it is almost overwhelmingly difficult to know where to lay ones focus for November’s post. In just a few weeks or so the peak mushroom season will be over, and then these monthly articles will be move away from our more typical looking types to the whatever crusts, rusts, slimes or jellies are out at any given time. At the moment, however, it seems like a Sisyphean task just trying to keep up with monitoring and capturing on camera the rich and colourful array of species appearing in brief successive waves in my local woods after spending so much of the year lying dormant – a task tinged with the sadness of knowing it will all be easing off again shortly. For this month, I’ve decided to split my focus between a mushroom that is undeniably striking, instantly recognisable and yet fairly commonplace, and a new documentary entitled Fantastic Fungi that sets out to explain why so many of us are smitten with this mysterious and, as we are now increasingly coming to realise, incredibly important aspect of our living world.

There can be few who fail to be impressed by the vibrant hues of the Amethyst Deceiver (Laccaria amethystina). It is but one of a number of types found around this time of year with a more pinkish, purplish or rosaceous colour that immediately makes it stand out against the muted palette of the late-Autumn woodland. I covered the Rosy Bonnet (Mycena rosea) and Lilac Bonnet (Mycena pura) this time last year. Other fetching fungi like my personal favourite, the Wrinkled Peach (Rhodotus palmatus) and the various Blewits, such as Lepista nuda, the Wood Blewit, are also commonly found throughout November. The deep purple hues of the Amethyst Deceiver, an ectomycorrhizal species that forms symbiotic associations with the roots of trees of all different types, and can be found amongst the damp leaf litter, particularly in beech woods, in abundance throughout Autumn, makes this one a very easy one to identify, even as the colours begin to wash out from the cap with age.

The amethyst hues permeate right through the flesh and stretch evenly to the gills and stem, even seeping into the mycelial fluff at its base. It is a small, delicate looking mushroom, the cap rarely getting much bigger than just over a centimetre in diameter and perched on a thin, fibrous, often twisting stipe that ranges from 5-10cm in length. The gills are deep and widely spaced, and either adnate with the stem, meaning attached to it, or emarginate, meaning slightly notched where they meet it. It is purported edible too, but with the stems too tough for consumption, the tiny caps don’t leave much for the pot if that’s where your interest in fungi lies, and most sources describe their taste as indistinctive. The other reason for not bothering with this as an edible is possible confusion with the Violet Webcap (Cortinarius violaceus), a species that is firstly incredibly rare and secondly belongs to a group of mushrooms that boasts some incredibly dangerous members.

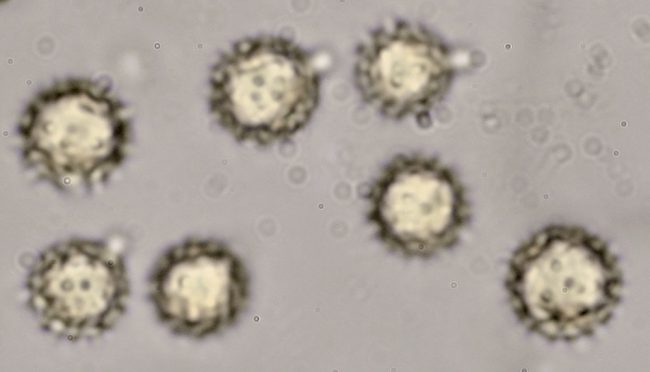

To be fair, while I’ve yet to chance upon a single Violet Webcap, comparisons with their descriptions in the guide books should put pay to any confusion. As well as scarce, Violet Webcaps are big and chunky, with the First Nature website describing a cap diameter between 6 to 12cm and a stem that can reach over 3cm in thickness at its club-shaped base. A spore print, in any case, will dispel any doubt. Typical for a Cortinarius species, the Violet Webcap will leave a rusty brown deposit, and this colouration manifests itself on the gills of older specimens. The spores of the Amethyst Deceiver are white – basically the only non-purple part of the mushroom. Get them beneath a microscope lens and they prove to be rather unusual: rather than ovoid, pip or tear-shaped, they are near enough spherical, and covered in tiny spines.

Amethyst spores

So why such an ominous sounding name, one might ask, given that they are so easily identifiable? It is because the Amethyst Deceiver has inherited the second part of its common name from the Laccaria group that it belongs too, specifically its close relation The Deceiver, or Laccaria laccata. The Deceiver is roughly the same shape and dimensions of the Amethyst Deceiver, but instead of purple, its colour ranges from brownish brick red through orange to salmon pink. In other words, it closely resembles the numerous species classified under the sobriquet of LBMs, or ‘Little Brown Mushrooms’ (or LBJs, ‘Little Brown Jobs’) – a catch-all term to describe mushrooms that are ubiquitous and nondescript enough not to warrant further inspection unless one really wants to dive deep down into the abyss of futility and frustration.

While The Deceiver’s varying hues and small, unremarkable appearance can cause some confusion in identification, there are enough tell-tale signs to separate the Laccaria from other mushrooms in groups like Entoloma and Tubaria that also fall within the LBM category. The trouble is really zeroing in to distinguish it from other members of the sizeable Laccaria group, such as Laccaria proxima or Laccaria bicolor, without wishing to head down the rabbit hole of microscope work. The Amethyst Deceiver, by contrast, has its deep-coloured purple hues to set it aside from its closely related fellow family members.

Laccaria

The case of The Deceiver perhaps highlights how a certain ennui can set in at a time of the year when the woodlands are liberally peppered with mushrooms of all shapes and sizes. I personally have a similar problem with Mycena, or the Bonnet mushrooms: I’m happy enough just to recognise a given example as belonging to the Mycena genus without the need to know which of the hundreds of possible specimens it is exactly. Mycology can be an exciting and rewarding hobby, but it can also be maddeningly cryptic. It is enough to make one want to retreat back into the house to spend the long, cold, damp autumn evenings doing something else, perhaps, like watching a film…

And so that brings me to the UK release of the American documentary Fantastic Fungi, which was meant to be getting a limited run in our cinemas from 6th November before the second lockdown shut them down again, as if demonstrating that making films is, if anything else, an even more frustrating endeavour than mycology. By extension, making films about mycology might well be seen as an inevitable path to madness.

The truth is that documentaries about the natural world have tended to be seen as the preserve of television over the years, particularly with the BBCs dominance in the UK. Standalone feature-length factual films on science are rare enough, and films devoted to fungi scarcer still. The mothballing of British cinemas means that the audience for Fantastic Fungi will be exclusively on the small screen, rather than the large one it was made for, but it is at least going out on a number of digital platforms, including Amazon Prime, Google Play and Apple TV, that should hopefully bring it to a wider audience (see here for UK digital release details). This demotion to the home cinema experience is inevitably going to prove a source of frustration for its director, Louie Schwartzberg, a cinematographer and time-lapse pioneer whose previous work, Mysteries of the Unseen World (2013), a 3D-IMAX film made in conjunction with National Geographic, played on some of the largest screens in the world. Fantastic Fungi certainly cries out to be seen on a big screen, with its beautiful time-lapses of various mushrooms and its computer-generated recreations of the hyphal networks stretching like a digital nexus beneath the forest floor clearly calculate to wow.

The truth is that documentaries about the natural world have tended to be seen as the preserve of television over the years, particularly with the BBCs dominance in the UK. Standalone feature-length factual films on science are rare enough, and films devoted to fungi scarcer still. The mothballing of British cinemas means that the audience for Fantastic Fungi will be exclusively on the small screen, rather than the large one it was made for, but it is at least going out on a number of digital platforms, including Amazon Prime, Google Play and Apple TV, that should hopefully bring it to a wider audience (see here for UK digital release details). This demotion to the home cinema experience is inevitably going to prove a source of frustration for its director, Louie Schwartzberg, a cinematographer and time-lapse pioneer whose previous work, Mysteries of the Unseen World (2013), a 3D-IMAX film made in conjunction with National Geographic, played on some of the largest screens in the world. Fantastic Fungi certainly cries out to be seen on a big screen, with its beautiful time-lapses of various mushrooms and its computer-generated recreations of the hyphal networks stretching like a digital nexus beneath the forest floor clearly calculate to wow.

Science documentary making is a tricky balancing act between delivering visual spectacle and enough factual information without overloading the viewer with a barrage of jargon. From a mycological point of view, Fantastic Fungi doesn’t quite get it right. Let me get one thing out of the way first - having co-directed a feature on slime moulds, The Creeping Garden (2014), I was somewhat dismayed to see numerous time-lapses of myxomycetes amongst the mushroom footage passed without any comment that they belong to an entirely different kingdom from fungi. Another issue is that the talking heads interviews with the experts who provide the film’s factual through-line can’t help but look rather mundane compared with the visual bombast on display elsewhere. Carrying the weight of the exposition and taking centre stage amongst the surprisingly select number of interviewees is Paul Stamets, and what one takes away from the documentary might well be largely down to ones prior knowledge of a figure who has proven somewhat divisive within the mycological community.

On the one hand, his evangelical zeal in espousing fungi’s ability to heal body and soul and all manner of planetary malaises such as mopping up environmental pollution and radioactive spills has proven undeniably infectious. There are many who would cite his highly popular book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World (2005) as their gateway into the field, myself included. To some others he is a snake oil salesman, who goes light on the science and is prone to exaggerated claims to boost his own enterprise, Fungi Perfecti, and Schwartzberg’s film has an unfortunate hagiographical air to it, with Stamets himself as the editor behind the tie-in book publication Fantastic Fungi: How Mushrooms Can Heal, Shift Consciousness, and Save the Planet. It is frustrating to see Fantastic Fungi diverge from the biological science and down the New Age route so early in its 80-minute runtime, with Stamets recounting an epiphanic psilocybin experience in some detail and attributing it to curing a childhood stammer. Celebrated “psychonaut” Terence McKenna is check-listed in a segment that reiterates his controversial claim that hallucinogenic fungi might have played a crucial role in the evolution of human consciousness. These sort of ideas are fine to throw in as one-liners to a documentary, I think, if presented as they are, which are hypotheses or opinions, not facts that have been submitted to a degree of serious scrutiny and validation. But around this midpoint, Fantastic Fungi gets derailed around into this kind of vague hypothetical pseudoscience, and subsequent claims about how certain mushrooms hold the cure for cancer feel laboured.

Despite my reservations, I would check recommend it as worth watching as a primer on fungi, a world that remains curiously invisible in everyday discussion. There are moments of wonder and beauty within it and if it encourages more people to delve into the subject, that can’t be a bad thing. The most important thing to bear in mind is that while not all of it should be taken at face value, the beautiful world presented onscreen is much closer to all of us than might be imagined. Take a wander out into the woods with a keen eye and an open mind, and it is all there for all of is. Indeed, there may be well a patch of Amethyst Deceivers not far from where you are now. Fantastic Fungi is in virtual UK Cinemas from 6th November and available on Apple TV, Amazon and Google Play from 9thNovember. More details of its release can be found here. You can check out the trailer here.

Comments are closed for this post.