October’s Fungi Focus: Ochre brittlegill (Russula ochroleuca)

It should be pretty easy, one would think, to recognise the various species within the Russula genus, or brittlegills, the bright-coloured little mushrooms that have been popping up vigorously across the country over the past few months. Their vibrant cap colours render them immediately conspicuous among the Autumn leaf litter surrounding the bases of the trees with which they form mycorrhizal relationships. while their shared features make them relatively easy to situate within this wide grouping. All are particularly prone to crumbling and breaking under rough handling and all have white or slightly off-white stems, gills and flesh, often exposed beneath the holes left in their vivid cap cuticles by snacking woodland creatures.

Russulas can be a maddening field, however, if you are among those who wish to pinpoint your finds more exactly. The genus is comprised of an ever-expanding and seemingly infinite array of species in which obvious visible features such as cap colour only play a partial role in identification. The name might derive from the Latin for red, but there’s a whole lot many more hues out there: purple ones, green ones, grey ones, yellow ones and numerous shades in between.

Russula silvestris (possibly)

One early guidebook for the casual naturalist, The Observer’s Book of Common Fungi (1954) by E.M. Wakefield, observed that “the species, which are many (in Britain nearly seventy), are not so well delimited”, listing just five common examples. The First Nature website gives photos, descriptions of distinctive features and other interesting information on several dozen. Mycologist Nicholas Money’s recent musings for a non-specialist readership, Mushrooms (2011), claims there are “750 of them, all with white gills, but with caps in every colour of the rainbow”, while Geoffrey Kibby’s The Genus Russula in Great Britain with Synoptic Keys to Species (2014 edition) provides the means for identifying “the nearly 160 species to be found in Great Britain”. While Kibby’s book is the best available for UK mycologists, one suspects his won’t be the final word on the subject.

Powdery Brittlegill (Russula parazurea)

Habitat is an important factor, of course. The little red-topped mushroom you might have found is highly unlikely to be a Beechwood Sickener (R. nobilis) if it has never been anywhere near a beech tree. It might be just a plain and simple Sickener (Russula emetica), if among conifers. Habitat only goes so far in providing definitive clues, however, because to give but one of many further possible examples, it might be a Russula silvestris, which grows in “solitary or in scattered groups on soil under broad-leaf and, rarely, coniferous trees”, as Michael Jordan describes in his The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe. The author also describes this latter species as “pallid pink or darker cherry red”, but even for the more colour conscious among us, there could clearly be some overlap with the “scarlet or cherry-red” he details for the other two, particularly in the muted light of a forest, whether the shadowy domain of the beechwood, or the varying colour temperatures associated with other wooded environments…

I should mention that I’m focussing on just these three species of red or reddish Russula to avoid unnecessary confusion. Within this region of the colour spectrum we can also find Rosy Brittlegill (R. rosea), Bloody Brittlegill (R. sanguinaria), Primrose Brittlegill (R. sardonia, confusingly named for the yellowish tinge to its gills) and many, many more without English common names, such as R. atrorubens (red but darker in the centre of the cap).

Probably Russula atrorubens due to the darker coloured centre of the cape, which has been nibbled to reveal the white flesh beneath

And let’s not even get into the thorny issue of white balance settings, filters and digital colour manipulation if you are trying to represent a particular specimen exactly “as is” in a photograph. There are a host of grey and other muddy off-white Russulas that similarly confuse. The best-known is the Charcoal Burner (R. cyanoxantha), but this is never a fixed pure grey and often displays a spectrum of underlying hues that can be exaggerated or downplayed in Photoshop. Pat O’Reilly in the species’ First Nature entry describes its cap as including “mixtures of violet, brown, yellow, blue, grey - all shades seen when charcoal burns”, while Jordan says the cap varies from “green to purple.” The fine dusty bloom on the cap of the otherwise very similar bluey-grey R. parazurea, meanwhile, is the most reliable key to identifying the Powdery Brittlegill.

It is a similar issue with gill, flesh and spore colour, all of which range considerably within the “white, not quite” parameters, with various species discolouring with bruising, breaking, oxidising and other age-related damage. Brittlegill specialists such as Kibby suggest making spore prints by leaving the cap facedown overnight then scraping the spores together so one can get some sort of critical mass in order to gauge whether they are pure white or just a “whitish” colour like cream or pale salmon.

The underside showing the brittle gills of a Powdery Brittlegill (Russula parazurea)

With colour hardly providing much of a firm base for identification, what other factors might we go on? Size, maybe? Returning to our little red ones, we see Jordan listing the cap of the Beechwood Sickener as 3-9cm, the Sickener as 3-10cm and Russula silvestris as 2.5-6cm – none of this is much help if your sample is, for example 5cm, or anywhere else within these midranges. We might legitimately ask who compiled the data for these sizes anyway, and make similar queries about stem dimensions and, even for those dedicated enough to get down to microscopic level, the overlap between the varying spores sizes of different species.

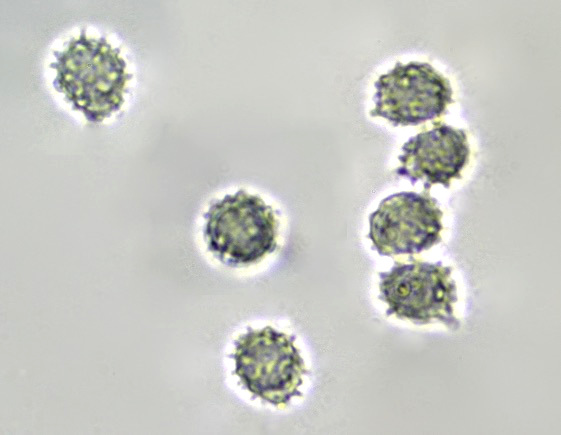

Russulas are pretty interesting under a microscope though. The spores have a knobbly, ridged or warty protuberances, with this ornamentation forming patterns or networks that can aid in the identification process. Nicholas Money’s Mushrooms mentions that even as far back as 1930, a book-length study The Spore Ornamentation of the Russulas had been compiled containing an exhaustive series of illustrations by a certain R. Crawshay.

Spores of unknown russula

Still, even at maximum levels of optical magnification (1000x magnification) it can be difficult to see the details really clearly enough without the aid of specific chemical reagents to bring out the features. Ah, chemicals, yes… More about these in a short while.

The flesh itself is also highly interesting under the microscope, as these Russula mushrooms are not formed out of the longer more fibrous cells that other fungi species’ fruiting bodies might be, but large spherical cells called sphaerocysts, giving it a texture Phillips describes as “granular”. This is why they break more cleanly than other mushrooms and the logic behind the name “brittlegill”. (The overarching family of Russulaceae also includes another genus alongside the Russulas. These are the Lactarius, or the milkcaps, which are also comprised of sphaerocysts, but exude a milky latex when their gills are broken). The degree in which the gills bend before they break is yet another feature used to identify different species, as is the extent to which the coloured skin on the upper surface of the cap can be peeled off. The cuticle of the Beechwood Sickener (R. nobilis) peels only 1/3 to the centre, O’Reilly reports on First Nature, while that of the Sickener (R. emetica) peels more than 2/3 to the centre. There is no mention of how far R. silvestris peels back.

The broken gills and peeling cuticle of a suspected Oilslick Brittlegill (Russula ionochlora)

Maybe our all-too-human reliance on vision and touch amongst the other senses will only get us so far with Russula identification. There are many among the mycological hardcore who suggest taking a nibble of your discoveries in search of further clues. The crucial point here is to taste, not to ingest, and spit out straight after. If such common names as the Sickener (or even the latin ‘emetica’) haven’t made it painfully obvious, most Russulas aren’t considered good eating. Quoting from a much general work by Geoffrey Kibby, Mushrooms and Toadstools: A Field Guide (1979), they “can be extremely hot to the taste when raw. Very few species are poisonous, although several are very indigestible or emetic if eaten in quantity.”

Flicking through the dozen or so pages of O’Reilly’s Fascinated by Fungi [https://www.first-nature.com/books/fungi2.php], we see the tastes of various species described as ranging from “mild” through “very acrid” or “bitter and hot” to “very hot” in the case of the Beechwood Sickener and “very hot and peppery” for the Sickener. Degrees of pepperiness or acridity are of course impossible to quantify objectively, but one can also turn to ones olfactory organ for assistance: the Purple Brittlegill (R. atropurpurea) reputedly smells “slight, of apples”, while the Crab Brittlegill (R. xerampelina) has the odour of “cooked crab” – although many a mushroom gets a bit fishy with age to my untrained nose.

The broken brittle gills of an Ochre brittlegill that something has been chewing or nibbling at with a tiny earthball at its base

What are tastes and smells anyway but indicators of chemical composition? This is where Russulas sort the sheep from the goats, as the more assiduous among fungi hunters seldom set foot in a woodland without their paraphernalia of specialist knives and hand lenses bolstered by a chemical arsenal of ferrous sulphate, ammonia, potassium hydroxide and other solutions that react by staining the flesh of specific species different colours.

It might all seem incredibly intimidating, but I think most of us would be quite content knowing whether we have found just a generic Russula or not and leave it at that. What is a common name or Latin nomenclature, after all, but a manmade indexical link for what is essentially the specific biochemical structure of the fruiting bodies of a certain species of fungi?

Russula identification skills are accumulated and honed over the course of many years, and I have to confess, I personally don’t have the patience. However, if you are lucky enough to be able to locate one of the rare individuals who have picked up this expert knowledge and present them with a specimen (or a photo thereof), they often just seem to know instinctively what you’ve got, the way one knows about a good melon. And with this in mind, I would like to give a quick hat tip to various members of the British Mycological Society Facebook group, in particular Geoffrey Kibby himself and Andy Overall, who have selflessly pointed towards the most likely identification for the various photos in this month’s post.

In the meantime, I nominate for October’s monthly mushroom the only Russula I can identify in my local woods with any confidence, the Ochre Brittlegill (Russula ochroleuca), also known as the Common Yellow Russula (due to it being incredibly common in the UK and yellow in colour). While many Russulas grow solitarily or in small groups, this one is usually found in large numbers in mixed woodlands, and the only thing you’re likely to confuse it with is the Yellow Swamp Brittlegill (R. claroflava), which has a stickier, more brightly yellow cap and is found on much damper ground.

A few closing notes regarding edibility: while many russulas will just burn your mouth out, there are a number that are listed as edible, of which Ochre Brittlegill is one, but from my own experience, it is so watery, insubstantial and tasteless, why bother?

Ochre Brittlegill

Indeed, this is my feeling about many mushrooms, but particularly with this group because many look so similar, and any slight genetic variation might have significant ramifications for those who ingest them. I mention this having recently read Money’s Mushroom book, because not only do we know that mushrooms can accumulate toxins from their environment (who knows what might be contained in the chemical runoffs from agricultural fertilisers that have seeped into the water table, for example), but that localised communities of fungi do seem to evolve their own specificities with regards to chemical compositions, of which toxicity might be an unforeseen by-product.

Money points out that “it is unlikely that any mushroom toxins are directed against us”, but mentions a number of specific cases of poisoning in recent years from the Yellow Knight (Tricholoma equestre), a non-Russula species considered good eating for many centuries – and which to the untrained eye could be mistaken with Ochre Brittlegill were it not for its yellow rather than white gills.  He argues that there may well be regional variations for the toxicity of this particular species due to the evolution of different genetic strains in different locations. By extrapolation we can say this for others species too: particularly with such an already diverse and difficult to identify genus as the Russulas. Every mushroom is different just like every person is different, and mushrooms and people don’t always agree with each other.

He argues that there may well be regional variations for the toxicity of this particular species due to the evolution of different genetic strains in different locations. By extrapolation we can say this for others species too: particularly with such an already diverse and difficult to identify genus as the Russulas. Every mushroom is different just like every person is different, and mushrooms and people don’t always agree with each other.

Humans are one thing, but I’ll just conclude by repeating the oft-made observation that squirrels seem to be immune to the hot taste and potential toxicity of Russulas, or maybe they just have more robust digestive systems and noses better suited to identification. They have regularly been observed “harvesting” brittlegills and leaving them in branches or laid out on tree stumps to dry and eat for later, so if you seem these mushrooms lying around partially nibbled in otherwise inexplicable places, this is the reason.

Comments are closed for this post.