The mysterious world of the Slime Mould

You may not be aware of it, but you are never far from a slime mould in the woods. You’ve probably seen one and dismissed it as some sort of noxious fungus. It is a common error, stemming from the misidentification by early naturalists that resulted in the misleading reference to mould within the name. Not plant, animal, nor fungi, these completely harmless life-forms actually belong to the single-celled group of organisms known as protists.

Although more commonly seen in Summer than Autumn, slime moulds can be spotted where you’d expect to find fungi; on leaf litter, fallen logs or dead vegetation - at least in the latter stages of their four-phase life cycle.

In the first stage, they exist as groups of individual cells that swarm around in the soil; they are invisible without a microscope. These then gather together to form their more conspicuous plasmodial stage.

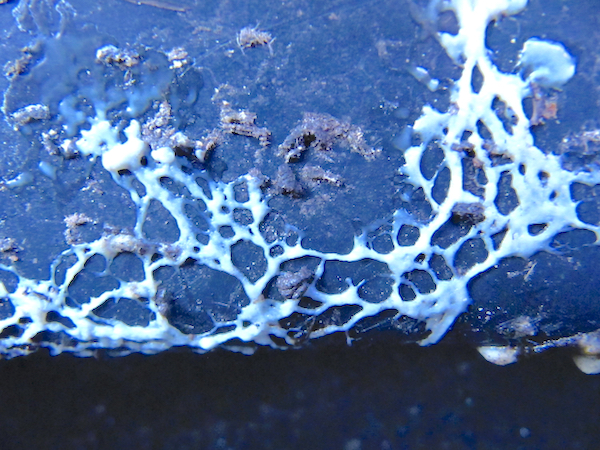

Plasmodium of dog vomit slime.

They appear as slimy blobs surrounded by oozy networks of cobweb-like patterns that are often strikingly beautiful in their intricacy, once you overcome the initial revulsion factor. The common names of Fuligo septica, known as either the Scrambled Egg or the Dog Vomit slime (see featured image above), perhaps provide some hint as to why the slime moulds might be so overlooked and understudied.

There are many fascinating aspects to these peculiar life-forms. As hinted by their grouping under Mycetozoa (literally, “fungus animals”), they, unlike fungi, are not rooted to one spot, but creep around in search of food (bacteria, natural yeasts and other organisms associated with decay).

Yes, they actually move, and while not fast enough for the naked eye to detect, if you come back after an hour, you’ll notice their patterns have changed. When the time is right, the oozy plasmodium coalesces to form the fruiting bodies that release spores into the atmosphere, giving rise to the next generation of slimes.

Yes, they actually move, and while not fast enough for the naked eye to detect, if you come back after an hour, you’ll notice their patterns have changed. When the time is right, the oozy plasmodium coalesces to form the fruiting bodies that release spores into the atmosphere, giving rise to the next generation of slimes.

The shapes and colours of the fruiting bodies, or sporangia, are what distinguish the hundreds of species [for an excellent guide on this subject see : Steven Stephenson’s Myxomycetes: A Handbook of Slime Molds (1994). Most of the slime moulds are known only by Latin names.

The slime moulds can appear in the form of the ochreish cankers of the Dog Vomit, the purple pustules of the Wolf’s Milk slime (Lycogala epidendrum)], or the pink-tinged ping-pong-ball swellings of the False Puffball (Enteridium lycoperdon), before they burst in a chocolate-coloured mass of spores. Most, however, manifest themselves as clusters of pinhead-like nodules on stalks. These can be tiny, but some more readily identifiable ones are the yellowish-brown dangling egg-shaped baubles of Leocarpus fragilis, the candy-floss like forms of Arcyria denudata, or the longer candlewick fingers of Stemonitis axifera].

Lycogala

The most remarkable aspect of the plasmodial stage is not only that they move, but that they move with purpose. This fact, first demonstrated by Japan’s Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki, when he discovered that they would always choose the shortest path in a maze leading to a food source, has led some to attribute them with a rudimentary form of intelligence. Not bad for a single-celled creature.

False Puffball

How such complex behaviour is generated in the processing between the multiple nuclei within this single-celled creature and how its computational power might be harnessed for some practical use is the subject of much research from such diverse figures as engineers, bio-artists, town planners, robot designers and computer scientists, much of which detailed in the recent film, The Creeping Garden and its accompanying book - Irrational Encounters with Plasmodial Slime Moulds.

So, next time you encounter intricate plasmodial patterns on a fallen log or in your compost bin, stop a while and pause for thought. You might have stumbled across a non-human sentient intelligence!

Comments are closed for this post.