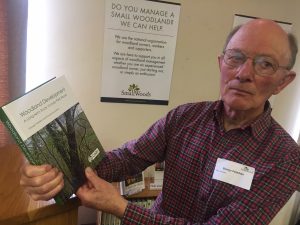

How George Peterken helped to save Britain’s ancient woodlands, and his new book – “Woodland Development”

I met up with George Peterken, the man who has probably done more than any living person to protect Britain's ancient Woodlands. He continues to study woods in fine detail to find out how they actually work and he has written a new book, "Woodland Development" where he explains how a 70-year study of Lady Park Woodland in the Wye Valley has revealed detail on how a broadleaved woodland develops. Young trees that are just slightly larger than others at the beginning tend to stay larger: "within the first decade, probably sooner, those which are destined to become big trees will have already established themselves as the larger saplings - it's like the boat race: getting an early lead means you probably win in the long run." In fact size matters generally and George Peterken's team established that "the chances of survival at any given time are proportional to your size." But the progression of Lady Park Wood over the last 70 years is not all as you might expect: of the trees that existed in 1945, three-quarters of them had gone by 2016 and all that was through natural loss.

Peterken's characterisation of how a woodland develops is quite like Stephen Jay Gould's idea of "punctuated equilibrium" in evolutionary biology. On most days the woodland is almost exactly as it was the day before, but occasionally a catastrophic event happens which brings about real, and sometimes sudden, change. In Lady Park Wood these major events included the 1976 drought, the start of Dutch Elm disease in 1971, major felling in neighbouring woodlands, the arrival of feral pigs, and intense attacks by grey squirrels in 1958, 1980 and 1992. But the future of a woodland is, in George's view, impossible to predict with any certainty. This is shown by the progression of his Wye Valley wood over the 30 years following its establishment as a reserve in 1945: initially it seemed to be moving towards beech dominance, but following the 1976 drought it looked as though lime and ash would dominate, but the beech came back and it then looked as though it would be a three-way outcome (lime-ash-beech). But with the recent shock of ash dieback it now looks as though it will become a lime-beech woodland. So events matter and are unpredictable, but Peterken

Peterken's characterisation of how a woodland develops is quite like Stephen Jay Gould's idea of "punctuated equilibrium" in evolutionary biology. On most days the woodland is almost exactly as it was the day before, but occasionally a catastrophic event happens which brings about real, and sometimes sudden, change. In Lady Park Wood these major events included the 1976 drought, the start of Dutch Elm disease in 1971, major felling in neighbouring woodlands, the arrival of feral pigs, and intense attacks by grey squirrels in 1958, 1980 and 1992. But the future of a woodland is, in George's view, impossible to predict with any certainty. This is shown by the progression of his Wye Valley wood over the 30 years following its establishment as a reserve in 1945: initially it seemed to be moving towards beech dominance, but following the 1976 drought it looked as though lime and ash would dominate, but the beech came back and it then looked as though it would be a three-way outcome (lime-ash-beech). But with the recent shock of ash dieback it now looks as though it will become a lime-beech woodland. So events matter and are unpredictable, but Peterken

believes that these punctuations to the background equilibrium are becoming more frequent. Peterken, one of the most knowledgeable woodland experts in the country, has got to the point where he now says, "it's a badge of honour not to make predictions any more - woodlands are unstable and unpredictable."

What he can say, however - based on his evidence - is that management generally increases biodiversity. He has compared woodlands which are simply left alone with those which are managed and the more neglected woodlands tend towards a lower species count. Also, he's found that dead wood takes time to build up - virgin forest has about 100 cubic metres of deadwood per hectare and it takes about a century for a newer woodland to build up to about this equilibrium level. In studying the development of a woodland, Peterken advises everyone to follow the advice of the 17th century diarist and sylviculturalist, John Evelyn, and make a written record of what you see. Indeed it was only because of the written record of early recorders in Lady Park Wood - such as Eustace Jones - that George Peterken and others were able to use a 70 year dataset for their study on which his "Woodland Development" book is based.

What he can say, however - based on his evidence - is that management generally increases biodiversity. He has compared woodlands which are simply left alone with those which are managed and the more neglected woodlands tend towards a lower species count. Also, he's found that dead wood takes time to build up - virgin forest has about 100 cubic metres of deadwood per hectare and it takes about a century for a newer woodland to build up to about this equilibrium level. In studying the development of a woodland, Peterken advises everyone to follow the advice of the 17th century diarist and sylviculturalist, John Evelyn, and make a written record of what you see. Indeed it was only because of the written record of early recorders in Lady Park Wood - such as Eustace Jones - that George Peterken and others were able to use a 70 year dataset for their study on which his "Woodland Development" book is based.

George is facts-focused, even when they present inconvenient truths. For example, he says that the Forestry Commission Public Relations department wasn't best pleased with him when he discovered that after Dutch Elm disease had become established the actual number of elms in his wood actually doubled (you get more, but they die young). He is very aware of the importance of perceptions of woodlands - another speaker at the Small Woods Association Conference, where I met up with Peterken,, said that it was a conscious effort which made Ancient Woodlands "a thing": such woods have gained their protected status because George Peterken, Oliver Rackham and Jonathan Spencer managed to create "a brand which others recognised". Instead of referring to Ancient Woodland as "scrub" and talking of "restoring it to productive use", they valued Ancient Woodlands for what they were and for their diversity. At the SWA conference Derek Niemann told the story of the "creation" of a new woodland in 1952 to mark Queen Elizabeth's coronation. Apparently it wasn't really a new wood at all - what they did was to fell an ancient woodland and plant it up with "productive" trees and announce that this was a new woodland!

George is facts-focused, even when they present inconvenient truths. For example, he says that the Forestry Commission Public Relations department wasn't best pleased with him when he discovered that after Dutch Elm disease had become established the actual number of elms in his wood actually doubled (you get more, but they die young). He is very aware of the importance of perceptions of woodlands - another speaker at the Small Woods Association Conference, where I met up with Peterken,, said that it was a conscious effort which made Ancient Woodlands "a thing": such woods have gained their protected status because George Peterken, Oliver Rackham and Jonathan Spencer managed to create "a brand which others recognised". Instead of referring to Ancient Woodland as "scrub" and talking of "restoring it to productive use", they valued Ancient Woodlands for what they were and for their diversity. At the SWA conference Derek Niemann told the story of the "creation" of a new woodland in 1952 to mark Queen Elizabeth's coronation. Apparently it wasn't really a new wood at all - what they did was to fell an ancient woodland and plant it up with "productive" trees and announce that this was a new woodland!

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Just raising a query. When he says that neglected woods tend to have a lower species count, does that include the life under foot and in dead lying wood or the plants and butterflies that are usually considered?

Good work Mr. P.

Dear Mr Peterkin,

Very interesting article. For the past 50 years we have lived on a hillside farm in Zambia with 450 Ha of fairly pristine miombo woodland and it has been fascinating to see the impact of the death of an old tree and the plant and tree succession that follows.

PS: Are you the George Peterkin who was in the London University rifle team in the early 1960s and studying the Ecology of Holly in the New Forest?

John E. Jellis

16 January, 2023