“The Scottish Uplands: how to revive a degraded landscape” a talk by Dr Helen Armstrong

Checking through my emails, I came across a link sent by a friend to one of the winter talks in the program offered by the Botanical Society of Scotland - specifically “The Scottish Uplands: how to revive a degraded landscape” by Dr Helen Armstrong. The talk was live-streamed but was also recorded and is available here.

Dr Armstrong spent 24 years at the Nature Conservancy Council, the Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Scottish Natural Heritage and Forest Research carrying out research and advisory work.

The following is an attempt to summarise some of the key features of her informative and enlightening talk.

Historical Background

The last ice age ended approximately 9000 years ago and, as the glaciers retreated, so a tundra-like vegetation of plants such as dwarf willow and juniper established itself. Trees then began to move in (first hazel, birch, willow, Scots Pine and aspen then oak, elm and alder), as did the first human hunter-gatherers. Gradually, a rich forested landscape developed, though trees were felled and clearings were made. The highland forest was probably at its greatest extent between 4000 to 2500 years ago. There was period between 3000 and 2000 thousand years ago when the climate cooled somewhat and Scots Pine dominated woodland contracted somewhat. As time passed, more woodland was cleared for farming activities. This continued up to about 1000 CE, at which time woodland cover has been estimated at 20%.

Throughout the following centuries, woodland cover continued to decline through human activities such as coppicing, pollarding and the creation of wood pasture until the sixteenth century when acts were passed to limit the deforestation; although charcoal then tanbark production continued in succeeding centuries. Gradually, sheep replaced cattle in the Lowlands and Highlands. The nineteenth century saw a fall in timber prices so sheep farming and grouse shooting increased and by the turn of the twentieth century woodland cover was probably at its lowest - about 6%. The lack of timber available at the time of the first world war - for mine props, fuel etc was a problem and most had to be imported. In consequence, the Forestry Commission was created, which embarked on massive program of tree planting - largely of coniferous plantations. Currently some 18 / 19% of the land area is woodland, but of this 14% is coniferous woodland; only 4% is native woodland and even less (1.5%) is ancient / relic woodland. Though these changes have been felt throughout Scotland, they have particularly affected the Scottish Uplands.

Throughout the following centuries, woodland cover continued to decline through human activities such as coppicing, pollarding and the creation of wood pasture until the sixteenth century when acts were passed to limit the deforestation; although charcoal then tanbark production continued in succeeding centuries. Gradually, sheep replaced cattle in the Lowlands and Highlands. The nineteenth century saw a fall in timber prices so sheep farming and grouse shooting increased and by the turn of the twentieth century woodland cover was probably at its lowest - about 6%. The lack of timber available at the time of the first world war - for mine props, fuel etc was a problem and most had to be imported. In consequence, the Forestry Commission was created, which embarked on massive program of tree planting - largely of coniferous plantations. Currently some 18 / 19% of the land area is woodland, but of this 14% is coniferous woodland; only 4% is native woodland and even less (1.5%) is ancient / relic woodland. Though these changes have been felt throughout Scotland, they have particularly affected the Scottish Uplands.

As woodlands were lost so were many plant and animal species. For example, the lynx (a top predator in the second or third century CE), wild ox or aurochs in the ninth / tenth century and at about the same time brown bears ‘disappeared’. In subsequent centuries, reindeer, moose, beavers, wild boar, wolves all vanished. This loss of species was compounded in Victorian times by the ‘eradication of vermin’ from estates. The ‘vermin’ included otters, ospreys, golden eagles, marsh harriers, kites, kestrels and buzzards (in large numbers), various owls and badgers. As trees and various animal species were lost, so the trees, grasses and herb layer changed.

Grass and moorland alongside the loch

Current land use in the Uplands

The Scottish Uplands now support four major uses of the land:-

- Forestry : whilst there are areas of natural Scots Pine woodland / forest, much of the woodland now is coniferous plantations (for example, sitka spruce) which is harvested by clear felling on 40 / 50 year cycle. There is little native woodland remaining in the Uplands, it has largely been replaced with commercial plantations. As mentioned above only 4% of the woodland can be regarded as native woodland in nature, even less is ancient woodland (dating from the 1700’s).

Sheep / hill sheep farming : black faced sheep are farmed in many areas and associated with this is the burning of tracts of land. This is done to encourage the regrowth of grass / vegetation in the Spring, giving a higher quality of forage for the sheep. There are often high numbers of sheep and grazing can be quite intense. That being said, sheep farming is on the decline partly as result of a change in the nature of the subsidies for sheep farming and the ageing population of sheep farmers.

Sheep / hill sheep farming : black faced sheep are farmed in many areas and associated with this is the burning of tracts of land. This is done to encourage the regrowth of grass / vegetation in the Spring, giving a higher quality of forage for the sheep. There are often high numbers of sheep and grazing can be quite intense. That being said, sheep farming is on the decline partly as result of a change in the nature of the subsidies for sheep farming and the ageing population of sheep farmers.- Grouse rearing / shooting : In order to manage grouse rearing / shooting, heather moorland is regularly burnt (on a 25 years cycle) to create a mosaic of heather plants at different stages of growth and development. This provides the best environment for grouse to feed and raise their chicks. Some 10% of the land area is used for grouse shooting and 4% of the land area is regularly strip burned. The areas are subject to culling of various animals which might take the grouse or their chicks.

- Deer / deer stalking : the two main types of deer in Scotland are red deer and roe deer. Stalking of red stags is particularly favoured by clients, so estates may feed stags in the winter months to maintain their numbers. However, other estates are trying to bring the numbers of deer down. Information on red deer in terms of numbers, age, weight, numbers culled / killed is limited. Similarly, data on roe deer are also quite limited, but is thought that their number has expanded in recent years.

deer damage

The impact on woodland areas

- In the last forty years, some 12% of ancient woodland has been converted to open ground through the grazing activity of deer. Much of this woodland has been in Upland areas.

- Some 33% of ancient woodlands are subject to heavy grazing so that natural regeneration does not occur. If this is allowed to continue, then these woodlands will ultimately disappear.

- About half of native woodland is subject to grazing that restricts tree and shrub regeneration to a greater or lesser extent. The more palatable species will disappear and the less palatable will survive, so the composition of the woodland will change. Montane scrub has been lost, bog woodland, treeline woodland and tall herb communities have been affected.

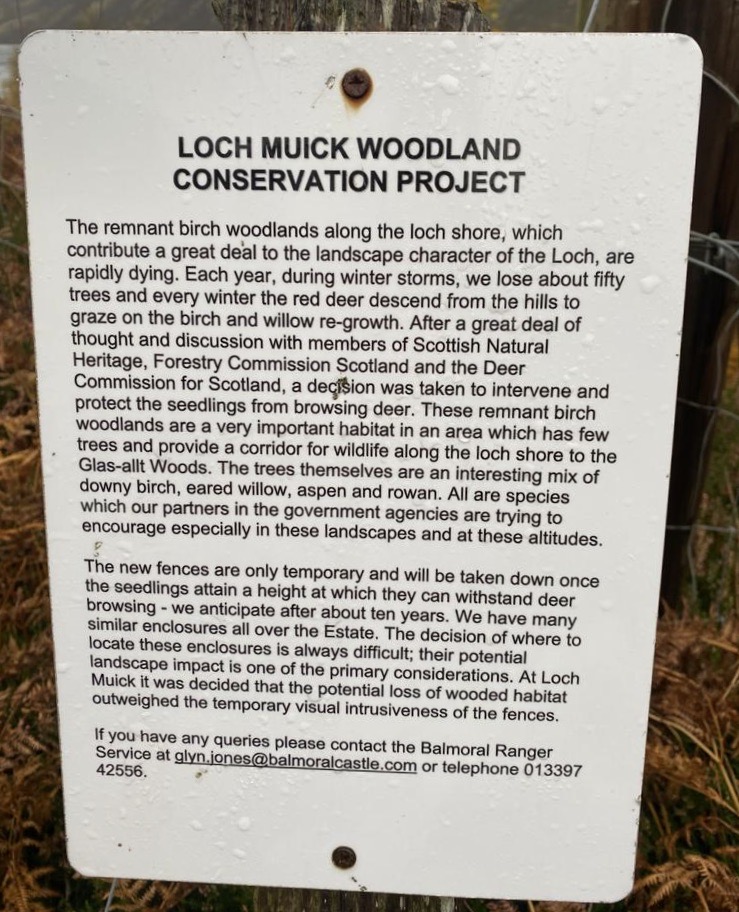

Remnants of birch woodland near Loch Muick are subject to browsing by red deer (especially in the winter), so temporary fences have been put in place to allow for regeneration. See also the photo at the end of this blog.

- In open grassland areas, the selective grazing by sheep has changed the species composition - increasing cover by unpalatable grasses such as Nardus stricta and Molinia caerulea. Consequently, forage quality is reduced. Vegetation structure and species diversity is reduced. Flowering and seed set is affected by the grazing, which in turn affects animal species, for example, insect pollinators and small mammals that feed on seeds. This loss of biodiversity, coupled with the historic loss of many key species, is worrying. Many areas can no longer support a diverse range of animals.

- Soils have become acidified (partly through peat formation but also the accumulation of conifer needles); soils have become wetter (trees tend to dry out soils) and leaching of nutrients has increased.

- Soil erosion has increased: soil gets washed into water bodies (streams, lakes)

- With the loss of tree cover, the risk of flooding increases. There is also the loss of shelter for animals such as deer, cattle etc; animals generally do better in woodland than in open / exposed areas.

- With decreasing biodiversity and structural complexity of ecosystems so the resilience of such systems falls.

The result is, to quote Dr. Armstrong “A landscape burned and grazed to the bone or smothered under dense conifers”. This is not a particularly new observation or conclusion, Sir Frank Fraser Darling wrote in The West Highland Survey - An essay in human ecology (1955) “The bald, unpalatable fact is that the Highlands and Islands are largely a devastated terrain”.

Can things be reversed / improved ?

Regeneration is indeed possible if

- Grazing by sheep and deer is reduced

- The burning of moorland is stopped or substantially reduced

- Trees and other species are planted - particularly in areas where there is no source of seeds

- Conifers plantations are diversified, made richer in species

Other things that might be considered are cattle grazing in areas where unpalatable species have taken a hold, as cattle are less ‘fussy’ than sheep. Also the re-introduction of lost / historic species could be considered. The most important thing is to restore the habitats so they can support more plant and animal species, to that end 1 and 2 (above) are the most important measures.

Where can this be done ?

Most of the Uplands could support woodland, there are only a few areas where this is not possible. In places where burning has stopped and grazing has been reduced, for example. on the Mar Lodge Estate and the Arisaig Estate , woodland has returned. At Ben Lawers, treeline woodland and montane scrub have been restored. What would a more wooded landscape offer? Increased

- Biodiversity

- Pollinators

- Shelter

- Wood products

- Recreational areas

- Resilience to climate change

- Resilience to pests and disease

It would also offer decreased :

- Soil erosion,

- landslides,

- silting of streams and lochs

- Flooding

Taking all of the above together, the areas should be productive biologically and economically.

Can it be done?

As with so many things, there is resistance to change - we like what we grew up with and know. This is often accompanied by the belief that change is impossible or indeed undesirable. However, change is possible as the above examples (Mar Lodge and Ben Lawers) illustrate. A lot of land is held by a relatively small number of people and central & local authorities have relatively little sway over the landowners of large estates. Landowners may wish to continue with the deer and grouse shooting and associated land management (as their land is sometimes valued in terms of its grouse shooting / stag hunting etc).

There are also problems associated with current deer legislation. Much of this is outdated having been put in place to protect deer, now it needs to focus on reducing deer density and protecting habitats. The Muirburn code, which concerns the burning of heather [for grouse or sheep], is voluntary. Landowners should not burn on bog, on steep slopes or high ground but this is not monitored. Grants and subsidies should focus more on the creation of more diverse and productive land. There needs to be investment in people and resources to bring about a richer and more diverse Highland environment.

The Loch Muick project is one of a number of projects that aims to restore natural vegetation to areas that have suffered from species loss

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

The following links might interest

https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/2018/05/how-to-make-birch-sap-syrup/

Is the tapping of the birch trees a possibility for making birch syrup or is it already practised?

A concise and informative paper, thank you. I believe that red deer numbers continue to rise unsustainably. Talk of reducing numbers has been going on since at least the 1980’s!

Come on, this is so serious, and also cruel, as many die of starvation in harsh winters. Culling programmes and Lynx introductions needed ASAP.

Barry O'Dowd

4 June, 2021