May’s Fungi Focus: Dock Leaf Rust (Puccinia phragmitis)

Spring is in the air and it feels as if the whole of the outside world has been painted over with a fresh coat of green. A new cycle of living plant matter means a new cycle of fungi that grow on and reproduce from this living plant matter. The few members of the kingdom that are conspicuous around this time of year can feel like an intrusion into this pristine world. I am talking about the rusts, the subject of previous postings on Blackberry Leaf Rust (Phragmidium violaceum) and Bluebell Rust (Uromyces muscari).

The rusts aren’t a particularly loved group, even among mycologists. Gardeners curse at the appearance of Puccinia allii on leeks, onions or garlic, or Puccinia menthae on mint, and as mentioned in my earlier pieces, Puccinia graminis, or Wheat Stem Rust or simply Stem Rust, has caused havoc with cereal crop yields. The very name “rust” hints at contamination, corruption and discoloration. However, they are a rather fascinating group to get familiar with, not to mention an important one, and they thrive around this time of year.

The purple spot on a dock leaf signals the presence of Puccinia phragmitis

Puccinia phragmitis is the focus of this month’s post, a species so obvious and common it seems bewildering that it hasn’t been given an English common name. Perhaps I should set the ball rolling and suggest the obvious, Dock Leaf Rust, because I suspect many reading this will have noted its presence in the form of roughly circular claret-coloured blotches that spring out against the verdant greens of the leaves of plants in the Rumex genus of docks and sorrels.

The cluster cups of the aecia of Puccinia phragmitis on the underside of a dock leaf in June of 2020

Turn the leaf over and you may be lucky enough, if they are developed enough, to spot the clusters of cup-shaped aecia (sing. aecium; the terms aecidia/aecidia are also used synonymously), the tiny fruiting bodies from which the spores, or more correctly, its aeciospores, are produced. These aeciospores, under the microscope, are white, circular, and 16-26 microns in size, about 2x3 times the size of a typical fungi spore.

However, this is only part of the story, as rust fungi boast up to five stages in their lifecycles, differentiated by specialists as Stage or Type 0, I, II, III and IV, with each forming different fruiting bodies that release different types of spores. Puccinia phragmitis goes through stages 0-III, and this purple blotch stage on Rumex leaves, the Type I or aecial stage, is when it is most eye-catching.

Aecia and aeciospores in Stage I of the lifecycle of Puccinia phragmitis

However, whereas with my other examples of rusts from the previous posts it is possible to watch the transformation between stages occurring on the same spot, this species presents a textbook example of a heteroecious rust, a rust fungi that jumps between different host plant species to complete its lifecycle, as opposed to an autoecious type that is restricted to a single host. Stage 0, in which spermatia spores are from spermogonia, and Stage I, in which aeciospores are released from aecia, occur on the dock leaf.

For stages II and III, however, this particular rust needs the presence of another host plant, the Common Reed (Phragmites australis). Invariable where one sees these purple pockmarked dock leaves, somewhere in the vicinity will be a pond or other wetland area full of reeds.

The Common Reed is the secondary host for Puccinia phragmitis

So the aeciospores are released into the wind from the dock leaves until they come into contact with a Common Reed, and here Stage II begins to develop over the summer months, the uredinia on which urediniospores develop. The uredinia take the form of reddish brown spots that grow in clusters on both sides of the reeds’ leaves sheaves and leaves, expanding linearly along their length, surrounded by a yellowish discolouration where the surrounding living cells die, and eventually rupture the outermost layer of cells known as the epidermis of the reed. From these, urediniospores are produced, but unlike the aeciospores, these can only infect the leaves of the same host plant on which they develop – so these will not go back to infect the dock leaves, only surrounding reeds.

The reddish brown uredia forming over Summer on the leaves of the Common Reeds caused by the thick-walled and warted urediospores

The urediniospores are yellow-brown, ovoid, thick-walled, warted, and slightly larger than the aeciospores, at 20-27×12-20 microns. They are responsible for the most evidently “rust-like” of the 4 stages in the lifecycle of Puccinia phragmitis, as they result in a visibly powdery surface for on uredinia.

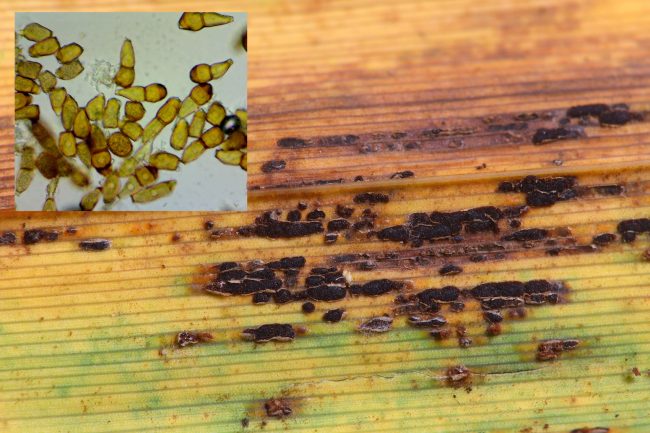

These urediniospores then go on to infect surrounding reeds, while the uredinia develop to Stage III, in which the fruiting bodies transform into telia that produce teliospores. The telia, it has to be said, look very similar to the uredinia, just larger and blacker, forming lines that stretch along the reed that can reach up to over a centimetre in length. The teliospores, however, are dramatically different; a much darker brown and consisting of two-cells with an extended stem, or a pedicel, that connects it to the telia, and much larger, at 32-55x16-26 microns. This means that when the stemlike pedicel is taken into consideration, these teliospores are almost visible to the naked eye, much like the large segmented teliospores of the Blackberry Leaf Rust (Phragmidium violaceum).

The uredia on either side of the reed leaf transform into black telia as the plant dies back over the Autumn

The teliospores effectively overwinter on the telia, on the dead leaves of the reeds, germinating in the Spring to form Type 0, the spermatia, that become airborne and float off to find a convenient dock leaf where they transform to Type 1 to form the aecia cluster cups on the lower side of the leave and thus the cycle begins afresh.

This type of dual host relationship is not unusual, and indeed, it is also shared by the

Wheat Stem Rust (Puccinia graminis), which alongside the grasses and cereals it causes so much damage to, spends part of its lifecycle elsewhere on the Common Barberry (Berberis vulgaris). Early on in the study of rusts, it became apparent that if one removed nearby barberries from wheat fields, the chances of crop damage diminished. (As always things turned out not to be quite as simple as that, but this is an area far too complicated for me to adequately explain here).

The black telia and segmented teliospores overwintering on a dead Common Reed leaf photographed in late-November

Rusts, as I shall reiterate from my previous posts, in most cases only cause cosmetic damage to the plants one sees them upon. Evolution is far too clever to come up with a parasite that spells rapid doom to its host. When the human hand comes into play, with the creation of monocultures that disrupt nature’s subtle balance, that’s when potential problems emerge.

Nevertheless, I hope this post draws some attention to the mutualism that occurs every day in the natural world, and how rusts can be just as interesting a field of focus as any other fungi. For those interested in the subject, I refer you to the book Roesten van Nederland / Dutch Rust Fungi, by Aad Termorshuizen and Charlotte Swertz, which contrary to the title spreads its net further beyond those species found in the Netherlands, most of which are the same as found in the UK anyway, and its text is in both Dutch and English. I also want to acknowledge the wonderful online resource Plant Parasites of Europe: Leafminers, Galls and Fungi, and its own entry on Puccinia phragmitis in helping me make sense of the photos I took over the course of the past year. There’s plenty of interest here to keep the curious nature lover amused over the coming months.

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Fascinating and enjoyable read.

The docks I found are right along side a large reed bed where I live in South Wales.

I will go back tomorrow morning to have a closer look now I know what I’m looking for.

Thank you

Fantastic article Jasper. It has set the ball rolling for me now!

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. I am truly fascinated by rusts. They are new to me. There are so many of them around the garden or nearby woods.

I don’t think about them as a disease but as beautiful structures that are fun to observe at the microscope.

Maricel

1 August, 2023